Post 2: John Winthrop and Roger Williams on Native Americans | Sangwon Yang and Mako Nagasawa

Pictured: Roger Williams and the Naragansetts, Wikimedia Commons.

The Purpose of A Long Repentance Blog Series

People talk about issues of race and justice in the United States as issues of ‘justice and injustice.’ Sometimes we launch into debates about ‘the proper role of government.’ But is that the original framework from which these issues were asked and debated?

The purpose of the blog post series called A Long Repentance: Exploring Christian Mistakes About Race, Politics, and Justice in the United States is to remind our readers that these issues began as Christian heresies. They were at variance from Christian beliefs prior to colonialism. Since Christians enacted and institutionalized what we believe to be heretical ideas, they were very destructive and harmful, then as now. And we bear a unique responsibility for them. As a result, we believe we must engage in a long repentance. We must continue to resist the very heresies that we put into motion. Thus the title of this blog series, A Long Repentance. The journey is long and challenging. It may be impossible to see the end. But along the way, it is also inspiring and sometimes breathtaking.

We also encourage you to explore this booklet, A Long Repentance: A Study Guide, for further reflections and discussion questions. Here’s a YouTube video called Colonization, Globalization, and Liberating Theologies where co-author Mako Nagasawa did an introduction and summary.

Christian Heresy as the Root of American Manifest Destiny and Evangelical Fears

Eric was starting to glimpse the sheer magnitude of the problem, even as he felt resistance to it. Bill was speaking Eric’s language about evangelism, too. He couldn’t argue that Bill had become a “liberal” in that sense. He clearly did care about presenting Jesus to people. So Eric ventured, “To partner with Native American Christians, do you think we need to address the legacy of colonialism? What do you think would happen to American culture?”

“You mean white American culture?” Bill asked. “We can choose between John Winthrop or Roger Williams on that, too. Winthrop wanted to create the ‘perfect’ church, and the ‘perfect’ Christian nation with the ‘perfect’ Christian government.”

“Okay,” interjected Eric. “But don’t we all want that? Don’t you?”

“Not in the sense you might mean it,” replied Bill. “Because as soon as you have a person who doesn’t believe, whether it’s your kid or someone else, church and nation become different communities. As soon as you have to ask someone to leave a church because of excommunication, even if done well, church and nation become different communities.[1] That’s why there is no such thing as a Christian nation. There are only Christians in a nation.”

“Okay,” said Eric. “I think I can agree with that. The other thing that could happen is if new people arrive, like immigrants. If the nation is “covenanted” with God, then immigrants are also a potential problem, right? Did that happen in John Winthrop’s “city on a hill”?” Eric asked, bracing himself for some less inspiring history.

“You’re spot on,” Bill agreed. “The Puritans wound up living in

“fear of what a wrathful God might do to them if they failed to keep their society pure. They were thus remarkably willing to believe that their society was in a constant state of decline. This was arguably the first American evangelical fear.””[2]

“Puritan fears were also on display in their relationship with the Native Americans who lived in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Conflict with Indians on the frontier was common in seventeenth-century New England. Some ministers believed that Indians represented the most concrete example of Satan’s efforts to destroy the city on a hill. According to this line of thinking, the century’s two major Indian wars -- the Pequot War in 1637 and King Philip’s War in 1676 -- were punishments from God for the Puritans’ failure to uphold their end of the covenant. Frontier missionaries, such as John Eliot and Daniel Gookin, established communities of “praying Indians,” but their efforts drew little attention from the powerful clergy who presided over the colony’s most influential churches. In fact, the evangelization of Indians often exacerbated already existing Puritan fears about Native Americans… The integration of Christian Indians into Massachusetts society was not an option that many Puritans were willing to entertain. As Puritans became more acquainted with Indian converts in their midst, the racial differences between the groups intensified in spite of the fact that both European and Native Puritans shared an orthodox belief and saw the necessity of godly living.

“By the end of the seventeenth century, Winthrop’s city on a hill seemed to be under threat. Massachusetts’ participation in the ever-expanding British transatlantic marketplace brought materialism and economic acquisitiveness to the colony. It brought “strangers,” who had no stake in the religious ideas at the heart of this colonial experiment…

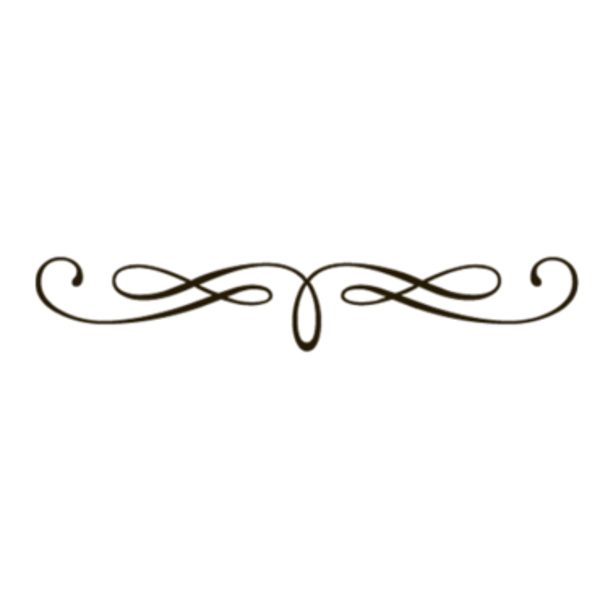

“Puritan fears about the moral and spiritual decline of their society reached a zenith in 1692. In that year 160 men and women in the colony were accused of witchcraft. Nineteen people were executed by public hanging, and one was pressed to death. The Puritan belief in Satan, demons, and witches only partly explains what happened in Salem and surrounding towns… Historians of both colonial America and early modern Europe have argued convincingly that witch trials were means by which religious and political leaders dealt with men and women who posed a threat to traditional Christian societies. Many of the Massachusetts residents who were accused by their neighbors of witchcraft -- and the clergy and prominent lay leaders who supported those accusations -- believed that the outbreak of malfeasance was a clear sign that satan was trying to deal a deathblow to their godly commonwealth. During the trials, Salem minister Samuel Parris preached from Revelation 17:14, reminding his congregation that “the Devil and his instruments will be warring against Christ and his followers.” [...] In fact… it would become a hallmark of evangelical thinking.”[3]

“Get this,” said Bill. “The fear-mongering, QAnon conspiracies, and end-times scenarios of evangelicals today were already happening back then.”

“In 1798, Jedidiah Morse, the congregationalist minister in Charlestown, Massachusetts, and a well-known author of geographic textbooks, drew national attention by suggesting that a secret organization called the Bavarian Illuminati was at work “to root out and abolish Christianity, and overturn all civil government.” He was convinced that this group of atheists and infidels were behind the secular Jacobin movement in France that sought to purge the nation of organized religion. Morse believed that the Illuminati group was pursuing the same clandestine agenda in America and was working closely with the Thomas Jefferson-led Democratic-Republicans, the Federalists’ political rivals, to pull it off… Soon Timothy Dwight, the grandson of Jonathan Edwards and the president of Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut, expressed similar fears about the Illuminati and used his pen to sound the alarm.”[4]

“Evangelicals were afraid of Catholics, unbelievers, skeptics, Masons, and deists because they thought that America was a Protestant nation always in danger of losing its Christian identity.”

Roger Williams, Religious Freedom, and Women’s Rights

“So you were also talking about Roger Williams,” said Eric, eager to change the subject. “I know Williams believed in freedom of religious conscience. He’s really the father of the First Amendment in the separation of church and state, right?”

“Yes,” replied Bill. “He welcomed people into Providence who had been declared heretics by the Boston Puritans.[5] He founded the first Baptist church in America. He created the environment for the first Jewish synagogue to start later on, in Rhode Island. One of my favorite stories about Roger Williams is the court case of Joshua Verins v. Providence Plantation.”

“What was that about?”

“Joshua and Jane Verins were a married couple who had settled in Roger Williams’ Providence. Jane wanted to attend the services of the local Baptist church. Joshua forbade her, on the grounds that he had that kind of power over her as her husband, according to his own religious belief. But the town council said Jane’s religious freedom was a higher principle than her husband’s religious claim.”

“The town met and formally reproved Joshua Verin for violating his wife’s freedom of conscience. The incident was the only disciplinary problem recorded in the colony's first two years of existence. The case, which occurred in May of 1638, is the first known record recognizing a woman's freedom of conscience in America. It thus appears to be the first time a legal precedent was established supporting the right of a woman to act according to her conscience, independent of her husband. This was quite a feat, as women of the Puritan time were thought of as servants of their husbands. Viewed against this backdrop, recognizing a woman's independence was an unprecedented act for the time, and a forward-looking vision of things to come.”[6]

“Wow!” Eric exclaimed. “Well, that would be consistent. The apostle Paul in 1 Corinthians 6 and 7 said that Jesus is the leading authority over the bodies of Christians (1 Corinthians 6:18 - 20). So even in Christian marriage, Jesus limits the claim of one spouse over the other (1 Corinthians 7:35).”

Roger Williams and Native Americans

“Bill, you mentioned how John Winthrop and Roger Williams regarded Native Americans differently. Was it because Winthrop envisioned a Christian nation vs. Williams envisioned Christians in a nation?”

“Winthrop called Native Americans savages,” said Bill. “He personally held three Pequot slaves. He believed they were culturally and racially inferior. He believed they should adopt English culture, and leave theirs behind, even if they came to faith in Christ. Like I said before, Winthrop used that cultural inferiority argument to explain to himself and everyone else why they could just take Native lands.”

“How did Roger Williams approach all this?” asked Eric. “Don’t Christians have to still influence the laws of a nation, state, city, or town?”

“Absolutely,” said Bill. “Christians can and should stand up for a general human rights platform.[7] But Roger Williams believed that Christians cannot set up a ‘perfect society just for Christians’ because we have not yet been morally perfected. Neither have our children. Or our neighbors. And, we have to be careful to not confuse our culture with Jesus.”

“What do you think will happen to our culture, then?” asked Eric soberly.

“Would it be so bad,” asked Bill, “If we learned more about environmental sustainability? If we resumed a conversation Roger Williams was already having with the Native Americans? For instance, after the massive California wildfires happened in 2017 and 2018, we found out Native people knew how to do controlled burns to prevent bigger fires. The Guardian titled an article, “Fire is Medicine: The Tribes Burning California Forests to Save Them.”[8] NPR titled an article, “To Manage Wildfire, California Looks To What Tribes Have Known All Along.”[9]

“I assume Roger Williams treated Native people better than Winthrop?” asked Eric.

“Yes, absolutely. Roger Williams also wanted to share Jesus with the Native Americans around him. He wrote a bestselling book about them because he learned their languages and even admired their culture.[10] Roger Williams said that Native men tended to treat Native women better than English men treated English women. He said the gap between what they said and what they did was smaller. In fact, in the mid 1600’s, the colonies of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Plymouth formed an alliance against the Narragansetts and Roger Williams’ Providence.”

“Why?” asked Eric.

“The Puritans thought they were heretics because they weren’t white Protestant theocratic, or early Christian nationalists. Providence was growing into a genuine community of white and Native peoples, structured by Christians who invited others in.”[11]

“So if we all had followed Roger Williams’ model, what do you think the United States would even be?” said Eric.

“Let me address an assumption you might have, Eric,” said Bill, “That we as white Christian people would only lose. What if we have a lot to gain?[12] To learn? And to remember?”

[1] Mark A. Noll, America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), chs.1 - 3 discusses this

[2] John Fea, Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2018), p.80.

[3] John Fea, Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2018), p.81 - 83. Of course, the English Puritans noticed that the Native Americans had various languages, cultures, and practices. They also recognized that Native Americans believed in spirits associated with nature. This could have led to a corresponding reflection on what the apostle Paul meant when he spoke of “powers and principalities, rulers and authorities in the heavenly realms” in Ephesians 1:21; 3:10; 6:10 – 12; Colossians 1:16; 2:15, 20; 1 Corinthians 2:6; and Galatians 4:8 – 10. The English Christians could have recognized a preliminary and appropriate creational diversity, to which sensitive and thoughtful Christian mission could have partnered with Native followers of Jesus into a Pentecostal diversity of tribes and tongues worshiping Jesus. But the “Christian nationalism” inherent in the idea of the Puritan covenant made this impossible. As Charles M. Segal and David C. Stineback, Puritans, Indians, and Manifest Destiny (New York, NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1977), p.35 write:

“New England tribes, as acknowledged by Protestant ministers like Roger Williams and John Elliot, deliberately structured their societies according to their natural environment. Their existence was so nature-based that it became, in their minds, suffused with spirits, or gods, that controlled their physical destiny as nations…

“Puritan religion was likewise sensitive to the totality of the natural world. A plague “meant something” to a Puritan as surely as it “meant something” to a Narragansett: everything in nature, from the point of view of both cultures, was to be noted and respected. Yet the notation systems that Puritans and Indians employed were alien to each other, since Englishmen found the meanings of natural events in the Bible [that is, as if the Puritan community was a politically covenant community like Mosaic Israel], not in acceptance of the natural world as a limited environment in which spirits and man interacted. For the Indian, civilized behavior was an acknowledged relationship with one's own natural world that necessitated respect, fear, and gratitude men could live in different circumstances and, therefore, have different civilizations. But for the Puritan, there was only one environment – God's – which left no room for the idea of different societies in different circumstances of equal moral value.

“In other words, like his American descendants on the moving frontier, the Puritan could not reasonably imagine the existence of native societies that were physically distinct from his own without being morally inferior period to him, nature was not another environment; it was a psychic realm which God allowed Satan to inhabit in order to demonstrate to his chosen people, who had turned nature into fields and cities, how difficult and fortunate their task was. From this point of view, the native inhabitants of the “wilderness” were both enemies of God's people and pawns in God's plan to remind His is people of their superiority to the natives. Only if the Indians’ dual purpose in Puritan eyes is understood – children of Satan and instruments of God – will the student of Puritan-Indian experience comprehend how desire to convert natives and readiness to kill them could be part and parcel of a single view of reality.”

[4] John Fea, Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2018), p.93 - 94. There is a strong correlation of witch trials with Protestant notions of a “political covenant.” If you believe that your city-state or nation is, or should be, “covenanted with God” in some way, dissidents become threats to your very existence. Consider this per capita data from Erasmus, “Witch Trials in the Context of the Reformation,” The Economist, January 21, 2018, also summarized by Jamie Coward, Why Europe’s Wars of Religion Put 40,000 ‘Witches’ to a Terrible Death. The Guardian UK, Jan 6, 2018.

The fact that in the political patchwork of German jurisdictions, leaders chose one or the other faith for their own purposes was also significant. Prior hostilities towards Jews also played a role. Yet the question at the intersection of theology and politics shifted from how might rulers demonstrate some degree of Christian ethics (mercy, financial support, personal integrity, etc.) to how a city-state or nation might demonstrate a nominal, abstract commitment to the Christian God at the expense of actual people and Christian ethics. In Switzerland, John Calvin’s city of Geneva became a theocratic police state, famously burning the heretic Michael Servetus at the stake, exiling others for such crimes as singing vulgar songs. In England, English Puritans had a notion of a national covenant imposed upon a country from the model of King Henry VIII; see the Witchcraft Acts in England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. In Scotland, the Presbyterian Scottish covenanters led by John Knox and James VI led to nationalistic religious purges: the five major Scottish witch trials between 1590 and 1662. In mostly Lutheran Finland, witch trials almost always resulted in acquittals, and most convictions resulted in fines.

Protestant hostility to Roman Catholics was in evidence on both sides of the Atlantic. The colonists’ reaction to the Quebec Act demonstrates the degree of Protestant Christian nationalism present in the colonies. The Puritan New Englanders viewed the Quebec Act of 1774 as the “establishment” of Roman Catholicism in Quebec, even though the Act merely permitted it. The Quebec Act, by which the British Parliament allowed French Canadians to retain their civil law even while it introduced English criminal law, also admitted Roman Catholics to citizenship and even public office. At the time, in the British colonies, only three colonies allowed Catholics to vote. In the New England colonies, only Rhode Island allowed Catholics to hold public office. New Hampshire law menaced with imprisonment all people who refused to repudiate the pope, the mass, and the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation. New York law threatened with the death penalty any Catholic priest who entered the colony. Virginia law threatened them with imprisonment. Georgia law did not allow Catholics to live within its boundaries. North and South Carolina law forbade Catholics from holding public office. Only Pennsylvania allowed Catholics to run their own schools. (Derek H. Davis, Religion and the Continental Congress, 1774 - 1789: Contributions to Original Intent (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p.153). It is notable that the Quebec Act was one of major grievances that led to the American Revolution. Political scientist Paul J. Cornish writes:

“The British settlers, like their forebears, were almost uniformly Protestant, holding anti-Catholic sentiments and opposing a legally supported system of hereditary nobility. They also were enraged by the Crown’s decision to deny their land claims in the Ohio Valley and believed that Britain had an interest in driving a wedge between them and their French-speaking neighbors to the north.

The Quebec Act did not succeed in rallying Canadians against the British colonies. Although the Second Continental Congress made provision in the Articles of Confederation (1781) for Canada to join the former British colonists, neither this provision nor American-launched invasions of Canada during the War of 1812 accomplished such a union.”

On the other side of the Atlantic, the Gordon Riots of 1780 in London provide evidence of strong Protestant anti-Catholic sentiment. Parliament’s Papists Act of 1778 was designed to confer more civil protections to Roman Catholic in Britain. But Lord George Gordon, a Scottish noble and sitting member of the House of Commons from 1774 - 1780, promoted a conspiracy theory: He argued that Catholics would join the British army and plot treason in conjunction with other Catholics on the continent, returning Britain to monarchical rule. Significantly, Lord Gordon was head of the Protestant Association of London, which was supported by leading Calvinist figures like Rowland Hill, Erasmus Middleton, and John Rippon. This institutional affiliation indicates widespread institutional and religious support. On May 29, 1780, Gordon called a meeting of the Protestant Association, which them marched on the House of Commons to demand that they repeal the Papists Act. In June, Gordon led a protest which devolved to widespread rioting and looting in London over several days, the most destructive in London’s history. The death toll was 300 - 700. The religious fear-mongering, Protestant populism, demagoguery, and conspiracy-stoking should be seen as common elements, later repeated in the United States and elsewhere.

[5] In 1637, Providence welcomed and assisted Anne Hutchinson and other dissenters, who had been exiled from Boston by the Puritans. Roger Williams helped them buy land from the Narragansett native people on fair terms.

[6] Edward J. Eberle, "Another of Roger William's Gifts: Women's Right to Liberty of Conscience: Joshua Verin v. Providence Plantations," Roger Williams University School of Law, Spring 2004; https://docs.rwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1015&context=law_fac_fs.

[7] Michael Gerson, “A Case Study in the Proper Role of Christians in Politics,” Washington Post, June 21, 2018; https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/a-case-study-in-the-proper-role-of-christians-in-politics/2018/06/21/39acd0bc-7578-11e8-b4b7-308400242c2e_story.html

[8] Susie Cagle, “‘Fire is Medicine’: The Tribes Burning California Forests to Save Them,“ The Guardian UK, November 21, 2019; https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/nov/21/wildfire-prescribed-burns-california-native-americans notes:

“For more than 13,000 years, the Yurok, Karuk, Hupa, Miwok, Chumash and hundreds of other tribes across California and the world used small intentional burns to renew local food, medicinal and cultural resources, create habitat for animals, and reduce the risk of larger, more dangerous wild fires.”

Early Puritan preacher John Cotton shows that the Puritans recognized the periodic land-burning that Native people carried out. Cotton notes, “They burnt up all the underwoods in the country, once or twice a year.” But they either remained ignorant of its significance, downplayed it, or disguised Native reasons when they portrayed the Natives as ridiculous. See John Cotton, A Reply to Mr. Williams his Examination, in James Hammond Trumbull, editor, The Complete Writings of Roger Williams (New York, NY: Russell & Russell, 1963), 2: 45 - 47, reprinted by Charles M. Segal and David C. Stineback, Puritans, Indians, and Manifest Destiny (New York, NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1977), p.81 - 82:

“We did not conceive that it is a just title to so vast a continent, to make no other improvement of millions of acres in it, but only to burn it up for pastime.”

Cotton wrote against Native claims to the land. He wrote also to ward off Roger Williams’ argument that God or King did not, and could not, in fact, give land to the Puritans. This suggests that the Puritans’ imperialistic and proto-capitalist designs upon the land led to a self-imposed ignorance about the significance of Native knowledge about the natural world.

[9] Lauren Sommer, “To Manage Wildfire, California Looks To What Tribes Have Known All Along,” NPR, August 24, 2020; https://www.npr.org/2020/08/24/899422710/to-manage-wildfire-california-looks-to-what-tribes-have-known-all-along writes,

“When Western settlers forcibly removed tribes from their land and banned religious ceremonies, cultural burning largely disappeared. Instead, state and federal authorities focused on swiftly extinguishing wildfires. But fire suppression has only made California's wildfire risk worse. Without regular burns, the landscape grew thick with vegetation that dries out every summer, creating kindling for the fires that have recently destroyed California communities. Climate change and warming temperatures make those landscapes even more fire-prone. So, tribal leaders and government officials are forging new partnerships. State and federal land managers have hundreds of thousands of acres that need careful burning to reduce the risk of extreme wildfires. Tribes are eager to gain access to those ancestral lands to restore traditional burning.”

[10] Roger Williams was a linguist who knew English, Dutch, French, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin before he learned Native tongues. He wrote A Key Into the Language of America: The First Book of American Indian Languages, Dating to 1643 - With Lessons Concerning the Tribes’ Wars, History, Culture and Lore, which won him much admiration in England.

[11] James A. Warren, God, War, and Providence: The Epic Struggle of Roger Williams and the Narragansett Indians against the Puritans of New England (New York, NY: Scribner, 2018)

[12] Bill McKibben, “After 525 Years, It’s Time to Actually Listen to Native Americans,” Grist, August 22, 2016; https://grist.org/justice/after-525-years-its-time-to-actually-listen-to-native-americans/ gives an environmental perspective.