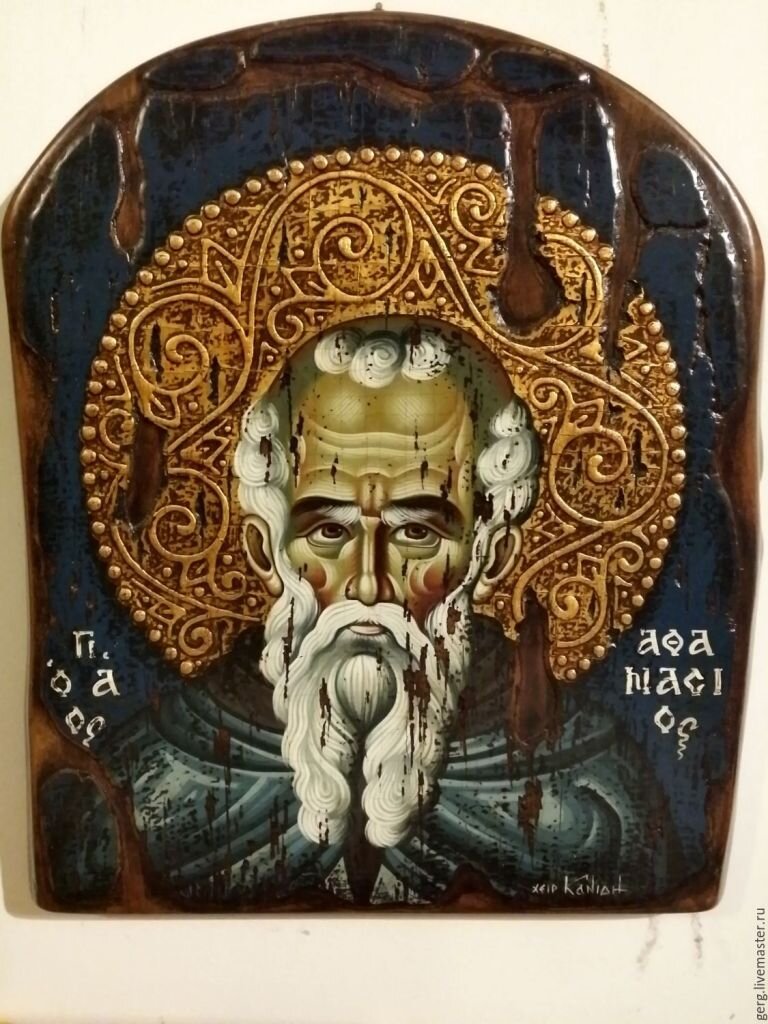

Athanasius as Evangelist, Part 9: God Haunts and Calls Us Through Our Own Words

God Works in Us Constantly

God haunts us through our language. He calls out to us through our own words.

Good and evil.

Love and selfishness.

Beauty and ugliness.

Justice and injustice.

Wholeness and brokenness.

These words point to realities larger than us. They are moral or ontological frameworks into which God placed us. Through these words, God involves us in those realities, and tugs on our hearts and minds.

C.S. Lewis, in Mere Christianity, and more recently Ravi Zacharias, have pointed out that if there are some things we would call evil, then there must be good also. And if there is evil and good objectively, then there must also be a moral lawgiver.

Trying to Break the Tether

Some people would like to silence the power of these words. For example, American philosopher Richard Rorty advocates that we abandon these kinds of discussions altogether, arguing that they are psychological mirages created by our language. Our language gives us the appearance of being placed in a moral universe larger than ourselves. If there really are such things as ‘good and evil,’ then that has implications for ‘human rights’ efforts around the world. Yet Rorty prefers to adopt a pragmatic attitude where we chalk up ‘human rights talk’ to simply ‘a culturally acquired taste’ of Western Europeans and Americans, that is, a white, Eurocentric culture.[1] Wittgenstein calls it a language game. In effect, Rorty wants us to say, ‘We do this simply because we like it.’

Athanasius would eschew Rorty’s view as an example of the hostility of the sinful human mind to God. Our language, he would say, bears witness to us that we live in a moral universe larger than ourselves. We are given to it, and it is given to us. He said:

‘For as of the Son of God, considered as the Word, our word is an image, so of the same Son considered as Wisdom is the wisdom which is implanted in us an image; in which wisdom we, having the power of knowledge and thought, become recipients of the All-framing Wisdom; and through It we are able to know Its Father.’[2]

The Son ‘is invisibly persuading so great a multitude from every side, both from them that dwell in Greece and in foreign lands, to come over to His faith, and all to obey His teaching’ (De Incarnatione 30.4), ‘pricking the consciences of men’ so that the adulterer is such no longer, and so on (30.5). But how does God do that? Through our own words and concepts.

The Mind Affected by the Exile from the Garden

Athanasius understands the fallen human intellectual problem in two distinct and interrelated ways. First, there is the problem of data. Prior to the incarnation, generally, human beings were not able ‘to get any idea at all of God, because while He was uncreate… and while He was incorporeal’ – for we could have ‘had knowledge of nothing but earthly things’ (De Incarnatione 11.1 – 2), ‘seeking about for God in nature and in the world of sense’ (15.2). The data of the cosmos, if we observe it alone, without interpretation from revelation, does not give us sufficient information to conclude that there is a loving, good God who wants to heal us and bring the cosmos in its entirety to renewal. In fact, atheists who live in the modern era with scientific knowledge such as the second law of thermodynamics would more naturally conclude that the universe is winding down. Left to itself, it will all become cold and dead.

If the material world and the tools of science were all we had to make conclusions about the character of God, then we would conclude that ‘god’ was toying with us. The universe and light and life was just a brief flash in the dark, but ultimately a tease and a trick. The ‘god’ behind such a narrative could only be callous and malicious. That ‘god’ ignites hopes for survival and eternity, but dashes them on rocks before all goes cold and dark.

We need a data point that gives us sufficient information about the one true God and His loving purpose to unite all things to Himself in a more profound way. We need the transfiguration and resurrection of Jesus.

The Mind Affected by the Corruption of Sin

Second, says Athanasius, there is the problem of damaged human perceptiveness. ‘Or how could they be rational without knowing the Word (and Reason) of the Father, in Whom they received their very being?’ (De Incarnatione 11.2) There is some mode in which our rational faculty is damaged, Athanasius says. Because we were created to be dependent upon, and relationally reflective of, the Word itself in creation, and the Word’s relation to His Father, the rupture caused by the corruption of sin actually damages our ability to think straight, at least about spiritual and theological matters. This is, perhaps, partially what the apostle Paul referred to when he said that the human mind ‘set on the flesh is hostile towards God’ (Rom.8:7).

Between the two main points Athanasius makes, the second requires a bit more explanation to moderns. Which is why I pointed out the attempts by secular philosophers Rorty and Wittgenstein to deny the impression that our own words give us, that we are born into moral frameworks larger than ourselves. Hostility towards God can express itself in the deconstruction of language.

Athanasius’ explanation for this hangs on the divine Word, human words, and our participation in rational language. An explanation from Scripture is required before I return to Athanasius.

Our Language Participates in God’s Rationality

Any serious attempt to grapple with the meaning of Genesis 1:1 – 2:3 must include the strong indication that language preceded humanity. Regardless of whether interpreters are trying to historically contextualize Genesis 1:1 – 2:3 relative to other Ancient Near Eastern literature, or demythologize it altogether, Scripture portrays God as possessing some form of language by which He said, ‘Let there be light,’ and welcomed human beings into that language. This remains an outstanding and intriguing question for scholars of all types. Neuroscience today, for example, suggests that the physical brain develops via language acquisition, and seems to be made for it. That God blessed humanity verbally (Gen.1:26 – 28) would seem to indicate that God created humanity with a built in capacity to understand the words of that blessing.

Then, as Adam named the animals, and other human beings later followed suit, he demonstrated the image of God by ordering the creation by speaking, just as God did in Genesis 1:1 – 2:3. Adam’s words apparently made a permanent mark on the history of the creation, for God Himself must have accepted the names Adam invented and used them. For example, ‘lion’ and ‘lioness’ became names God used henceforth, too. ‘Cain,’ ‘Abel,’ and ‘Seth’ were the names God used henceforth, too. Experiencing God use the names that human beings named animals and children must have been rather astounding. Our special role is to be drawn from the earth to give creation voice in rational praise to God. In this way, the non-human creation is drawn up into the human by a temple arrangement, as people say out loud what the rocks say silently. And the words of praise spoken by human beings deepen as the words ‘thank you’ and ‘thank You, Lord,’ overflow with more meaning every time we utter them.

In fact, Adam and Eve still had yet to forge, or receive, and experience certain words, such as the word ‘word.’ How could human beings have confessed, ‘The Word was God,’ before they themselves spoke in such a way that ordered creation within the happy commitment of God Himself to use those very words? ‘God calls them lion and lioness, too, and uses the name we gave our child.’ They needed to speak, observe the impact, and then reflect rationally on the very act of speaking. If their speech had this impact, then what impact did God’s speech have? What is God’s speech? Or, how about the word ‘beget’? How could human beings have confessed, ‘The Father eternally begets the Son,’ before they themselves had begotten a child? What does it say about God’s purpose in creation that the doctrine of the Trinity – as in, our human ability to articulate and understand it – depended on human obedience to God’s creational command to be fruitful and multiply, our experience of childbearing, and the further development of language, in partnership with God, that would provide the adequate categories to even begin reflection on it?

Perhaps the distinction between ‘nature’ and ‘grace’ as developed in the West should be declined as a false opposition. Is human language part of ‘nature’ or ‘grace’? Nature already is grace, and expects more grace. In fact, nature articulates grace, because grace has stamped itself indelibly upon nature while calling nature to experience more grace. This is well within the Eastern Orthodox understanding of the ‘divine energies.’ Human beings already participate in the rationality of language, for we were made ‘in him,’ that is, ‘in the Word’ (Col.1:17; Acts 17:28). And thus, it is in the creative Word and through human words that God already anchored His own self-giving to humanity, through the agency of human beings and the words we utter back to God, to provide for the return of God to God in a structure of ever-increasing fullness.

If rational language and concepts existed with God prior to humanity’s creation, human beings had to learn that language and those concepts by experience. At least two second century Christian writers strongly suggest this awareness – important to note because both of them came from Asia Minor, which was the mission field of the apostles, intentionally.[3] In other words, the minds of Adam and Eve needed to be gradually filled by experiential knowledge which they could coordinate with the abstract words God shared with them from the outset.

Human Being and Human Becoming

The human mind itself needed to be filled. God anchored those words in the human mind, and probably some very preliminary sense of their meaning. But the meaning of those words could only be filled out in the divine-human partnership. Elsewhere, in Discourses Against the Arians, Athanasius uses the terminology of God’s Son as Word and Wisdom impressing itself upon the human mind in creation, so that we might be capable of knowing the Father, and thus, ‘not only be, but be good’:

‘Now the Only-begotten and very Wisdom of God is Creator and Framer of all things; for ‘in Wisdom have You made them all,’ he says, and ‘the earth is full of Your creation.’ But that what came into being might not only be, but be good, it pleased God that His own Wisdom should condescend to the creatures, so as to introduce an impress and semblance of Its Image on all in common and on each, that what was made might be manifestly wise works and worthy of God. For as of the Son of God, considered as the Word, our word is an image, so of the same Son considered as Wisdom is the wisdom which is implanted in us an image; in which wisdom we, having the power of knowledge and thought, become recipients of the All-framing Wisdom; and through It we are able to know Its Father.’[4]

If Athanasius’ reading of creation and language is correct (and if my reading of Athanasius and Scripture is correct as well), then the pull of the rationality of language is itself a force that exerts itself upon us. For human beings to have linguistic categories of ‘good’ and ‘evil,’ especially, immediately places us into a world where we are the inhabitants of a moral framework larger than us, which exerts itself upon us and reaches into our very being. In fact, it also emerges from our very being. This force is not trivial.

Athanasius is saying that in order for our minds to have any hope at all of rationally apprehending God, God must have impressed His own rationality upon us in the creation, and specifically through language and our ongoing development of language.

And, to ‘become recipients’ of God’s Wisdom, we have to exercise the power of knowledge, thought, and even language. That power increases and develops with right usage. God could not automatically supply all the experiential knowledge necessary for Adam and Eve to personally grasp the full meanings of those words as understood by God Himself, precisely because He cannot lie (Heb.6:18) and manufacture false memories.

Words like ‘good’ and ‘beauty’ and ‘love’ and ‘justice’ are anchored and framed in the human mind by God, but we must fill those words with appropriate and increasing content in partnership with Him. The Word-Wisdom of God, as Athanasius says, did ‘condescend to the creations, so as to introduce an impress and semblance’ of God’s wisdom in our minds, in which, and through which, we grow.

[1] Richard Rorty, ‘Human Rights, Rationality, and Sentimentality,’ note 43, at p.116. Michael Perry, The Idea of Human Rights: Four Inquiries (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), p.38 – 39 offers a good critique of Rorty.

[2] Athanasius of Alexandria, Discourses Against the Arians 2.78 emphasis mine

[3] Irenaeus of Lyons, Against Heresies 4.38.1 refers to Adam and Eve as ‘infants.’ John E. Toews, The Story of Original Sin (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2013), p.50 credits Theophilus of Antioch (d.183 – 185 AD), Letter to Autolycus 25 with being the first to write that Adam had been nepios, ‘a child,’ and needing to properly mature. Irenaeus repeats that in Demonstration of the Apostolic Preaching 11, 14. I suspect that Theophilus and Irenaeus meant that Adam and Eve were mentally, not biologically, children.

[4] Athanasius of Alexandria, Discourses Against the Arians 2.78 emphasis mine