Post 2: Donald Trump’s Scapegoating and the Scapegoating of the Black Community

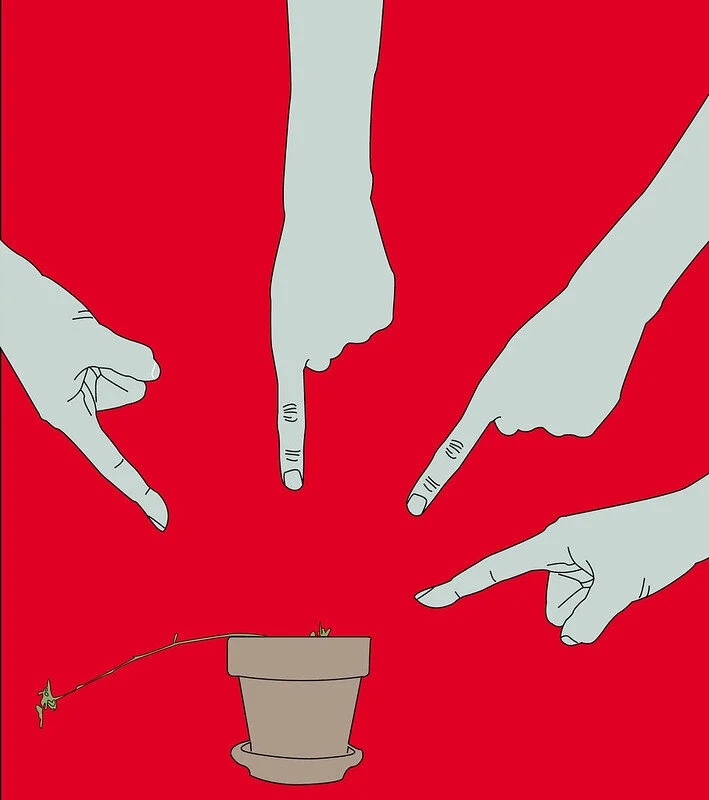

“Blame” by 周小逸 Ian. Creative Commons 2.0.

U.S. History and Scapegoating by Conservatives and Liberals

Let’s look at how Rene Girard’s definition of ‘scapegoating’ (as in, blaming one instead of the community) takes place in American public life. Scapegoating is politically effective. It is continually reinvigorated by American political campaigns. On December 21, 2015, The Washington Post observed:

‘The same rhetoric that frightens critics (“Trump has really lifted the lid off a Pandora’s box of real hatred and directed it at Muslims,” said the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Mark Potok) draws praise from supporters such as former Louisiana politician and KKK Grand Wizard David Duke. Duke told The Post that while he has not officially endorsed Trump, he considers the candidate to be the “best of the lot” at the moment. “I think a lot of what he says resonates with me,” Duke said… Stormfront, one of the most popular white nationalist websites, claims that a surge of Trump-inspired traffic has forced administrators to upgrade their servers, according to Politico.’[1]

When Donald Trump claims that he can ‘Make America Great Again,’ and Ted Cruz says he is about ‘Reigniting the Promise of America,’ we are invited to return to a mythical American past. But these conservative mantras not only overlook the problems woven deeply into the legal and cultural structure of the U.S. They also require that we ask the questions, ‘Who made America not great? And how did the fire go out?’ and answer them implicitly with, if not ‘Barack Obama,’ then ‘liberals and immigrants.’

Conservative romantics look at time differently than progressive optimists, who, like their Enlightenment forebears, see history as a continuous narrative of development. For progressives, that development is slowed only by conservatives with their irrational and often religious affection for the past.

Both narratives are parodies and reversals of the actual biblical story. The conservative camp parodies the biblical story by envisioning America’s colonial beginnings as a pre-fall garden of Eden. The progressive camp parodies it by envisioning the comforts afforded by technology and individualism to be the secular equivalent of the New Jerusalem, the garden city. Neither narrative is actually Christian. And both narratives require a scapegoat: the other side, mainly.

For various reasons, white evangelical American Christians tend to feel more affection for the conservative myth. So much so that they are willing to overlook history, or even rewrite it. Take for example historian David Barton, who is now allied to the Ted Cruz campaign:

‘When Cruz says he wants to “reclaim” or “restore” America, he does not only have the Obama administration in mind. This agenda takes him much deeper into the American past. Cruz wants to “restore” the United States to what he believes is its original identity: a Christian nation. But before he can bring the country back to its Christian roots, Cruz needs to prove that Christian ideals were indeed important to the American founding. That is why he has David Barton on his side.

‘For several decades Barton has been a GOP activist with a political mission to make the United States a Christian nation again. He runs “Keep the Promise,” a multimillion-dollar Cruz super-PAC. He’s one of Cruz’s most trusted advisers. Barton is the founder and president of WallBuilders, a Christian ministry based in his hometown of Aledo, Texas. He writes books and hosts radio and television shows designed to convince evangelicals and anyone else who will listen that America was once a Christian nation and needs to be one again.

‘But his work on the history of the American founding has been discredited by historians, many of whom are his fellow evangelicals. This does not seem to stop him. His 2012 book, The Jefferson Lies: Exposing the Myths You’ve Always Believed About Thomas Jefferson, was roundly condemned for its historical inaccuracies and its attempt to turn the third president of the United States into a member of the 20th-century Christian right. Thomas Nelson, the book’s publisher, pulled it from print.’[2]

The opposite myth, often implied by liberal media sources who uphold the narrative of progressive optimism, tends to reduce to the narrative of ‘the dysfunctional South.’ People in the South are less educated, shows one news source.[3] Perhaps that is why they refuse Obamacare and vote against their own economic self-interest. Or why they remain ‘the Bible belt.’ The South is home to Confederate flag wavers who believe the Civil War never really ended, says Salon.[4] The South (alone, one asks?) rewrites history about slavery, the Civil War, and ‘states’ rights’ to diminish their own racism, say the Washington Post and the New York Times.[5] There are quite a few indications that the secular liberal scapegoating of religion and tradition is silencing debate on college campuses, the very place where it should be taking place.[6] In my opinion, this seems to be a ‘campus as fortress’ mentality of secular liberals in response to the ‘nation as fortress’ mentality of conservatives not too long ago. I’ll address the secular liberal myth in later posts.

But while these observations raise legitimate concerns, in my opinion, they too are a form of scapegoating. For they tend to exonerate ‘the North,’ and other sections of the country, from their own racism and responsibilities, and claim a foundation for human dignity and human relations without intellectual foundation. Robert Tracy McKenzie, a professor of American history at Wheaton College and an evangelical Christian, notes that both the North and the South developed myths to blame the other side for the Civil War. Neither myth is true:

‘The claim that America “fought the most devastating war in its history in order to abolish slavery” is a masterful enunciation of what I have previously labeled the northern myth of the Civil War…’[7]

‘Boiled down to its essence, the southern myth depicts the war as the culmination of a philosophical struggle over the rights of states in the American Constitutional system. Slavery was at best coincidental to this struggle, which might just as well have come over mules, as one southern apologist famously contended near the close of the nineteenth century. In contrast, the northern myth defines the war as a moral crusade to remove, at long last, the blight of human slavery from the American republic… By making the South a sectional scapegoat for a national problem, the rest of the country has been able to reassure itself that racism is an aberration, a pathology limited to the country’s one sick region.’[8]

Journalists Anne Farrow, Joel Lang, and Jenifer Frank note in their 2005 book Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited from Slavery the deep, entangling dependence of Northern cities, merchants, and governments on Southern products made with slave labor. Ivy League universities, too, today’s bastions of secular thought, profited a great deal from slavery, and seem unsure what to do with that inheritance.[9]

Historian Gerald Horne asks us to look even further back. In his 2014 book The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America, Horne argues that the American Revolution itself should be understood, not only as the purely-motivated heroic struggle of ‘liberty’ against English tyranny, but also as an escape from the growing British slave abolition movement:

‘In June 1772, in London, there was Somerset’s case [granting the black slave Somerset his freedom], which seemed to suggest the case’s initial meaning, which of course was for England, could be extended across the Atlantic to the colonies. This caused great consternation in the colonies, not the least since the colonial economy was underpinned by slavery.’[10]

‘The so-called Revolutionary War, Horne writes, was in large part a counter-revolution, a conservative movement that the founding fathers fought in order to preserve their liberty to enslave others—and which today takes the form of a racialized conservatism and a persistent racism targeting the descendants of the enslaved.’[11]

How can we account for this? I believe at least one historical narrative needs to be the narrative of Christian mission, including the Christian struggle of orthodoxy against heresy. By the 1300’s, Christians, in faithfulness to the biblical texts, had abolished slavery in northern and northwestern Europe.[12] They did so by struggling against specific and illicit ways by which people became enslaved, and by shutting down the trading in persons. However, in the 1400’s, Western European Christians brought about the reemergence of slavery, and chattel slavery at that, by going around Africa to trade with India but not the Ottoman Empire, and taking over Arab Islamic slave trading in African coastal cities.

Since the British abolitionist movement was spearheaded by Christians, the pro-slavery secession in the American colonies should best be understood as an outgrowth of heresy. Evangelical historian Mark Noll, in his smartly titled book The Civil War as a Theological Crisis, makes the more precise judgment that it was a Protestant and American heresy:

‘Irish evangelicals and many other foreign Protestants simply took for granted that the Bible ruled out slavery… Outside the United States, one rarely encountered the conviction that to trust the Bible meant to approve, however reluctantly, the slave system in its American form… In the vast majority of cases, foreign Protestants took note of biblical arguments in support of slavery only to dismiss them.’[13]

‘[Roman Catholics abroad went further.] They questioned the link taken for granted by many Americans (and described memorably by Alexis de Tocqueville) between expanding liberal democracy and flourishing orthodox Christianity. They suggested that the Protestant embrace of unfettered economic freedom actually damaged Christianity. They asked whether American definitions of liberty were the only, or the best, formulations for modern societies. And as a special contribution to debates over Scripture and slavery, they dared to wonder whether Protestant American individualism might not account for the sad fact of confusion in the interpretation of sacred writings.’[14]

When we see history in this light, we cannot possibly maintain the popular conservative story of U.S. origins as a ‘garden of Eden’ of freedom and liberty. Nor can we maintain the popular progressive story of people breaking free of the shackles of slavery, poverty, and religious irrationality into the utopia of ‘social justice.’ The scapegoats offered by both camps are invalid. For the myths they hold out are untrue.

Instead, I suggest that U.S. history, at least partially, should be told as the slow recovery of a pocket of European Christian civilization which long resisted authentic discipleship. We can trace the church’s remarkable struggle for human dignity and against slavery from the first century, even when particular Christians are implicated in wrong-doing or wrong-thinking. If we take the British Christian abolitionist perspective as the immediate locus of that struggle, then we see the American Revolution and the American Civil War as the efforts of heretical Protestants trying to escape the ramifications of authentic Christian discipleship. We can also interpret secular liberalism partly as the result of people’s distaste with American Protestantism after the Civil War: understandable perhaps, but deeply mistaken as well.

White Supremacy as the Scapegoating of Black People

Also in light of this global narrative involving the church, human dignity, and slavery, we can better understand the ideology of white supremacy throughout U.S. history. For various reasons, many Europeans originally associated black skin with impurity, inferiority, and lack of Christian civilization. Because of longstanding European tradition where conversion to Christianity gained an enslaved person his freedom, ironically, European merchants and powers needed to find non-Christians to enslave. Also, European-American plantation owners wanted to make slavery pragmatically easy.[15] It was easier to identify black people. For example, after Bacon’s Rebellion (1676), Virginia elites began to buy more African slaves as opposed to gathering other European poor, vagabonds, dissenters, convicts, and prisoners of war who also served as indentured servants in the colonies. So behind white supremacy lay the myth of white superiority and innocence along with the resurgent myth of slavery populated by criminals as part of the natural order of things, and the corresponding myth of black criminality. That is how European-Americans elites provided themselves with a rational and moral defense of slavery and racism. White supremacy used a scapegoating device.

Consider this: White Americans dressed black slaves in the garb of criminality: chains, because prisoners in Europe wore chains. Whites executed blacks in the manner of criminals: lynchings, because notorious criminals in Europe were executed by hanging. The images of criminality and threat were constantly imposed upon black Americans. After the Civil War ended and black people in the South went free, white Southerners invented draconian lending laws to make black people into formal criminals, and used ‘convict leasing’ to enslave them again for profit under the exception clause of the 13th Amendment (pioneered, incidentally, by Northern whites in New York[16]). Discriminatory housing practices and laws were driven by fears of ‘dangerous black people.’ So have been the overly punitive policing and drug prosecution in this era of mass incarceration.[17] Ronald Reagan’s famous ‘welfare queen’ image was implicitly an image of a black woman illegally bilking the system.

I believe Girard’s theory would regard all of the above as scapegoating black people for being moral, if not legal, transgressors. This is not just one mental association among others which can be teased out from racial bias. The suspicion of moral failure, danger, and lurking criminality is the emotional and rationalized basis for racial bias itself:

‘White Americans overestimate the proportion of crime committed by people of color and associate people of color with criminality. For example, white respondents in a 2010 survey overestimated the actual share of burglaries, illegal drug sales and juvenile crime committed by African-Americans by 20 percent to 30 percent.’[18]

‘Implicit bias research has uncovered widespread and deep-seated tendencies among whites – including criminal justice practitioners – to associate blacks and Latinos with criminality.’[19]

‘Lisa Bloom, in her book “Suspicion Nation,” points out: “While whites can and do commit a great deal of minor and major crimes, the race as a whole is never tainted by those acts. But when blacks violate the law, all members of the race are considered suspect.” She further says: “The standard assumption that criminals are black and blacks are criminals is so prevalent that in one study, 60 percent of viewers who viewed a crime story with no picture of the perpetrator falsely recalled seeing one, and of those, 70 percent believed he was African-American. When we think about crime, we ‘see black,’ even when it’s not present at all.”’[20]

Once again, this myth of black criminality flies in the face of actual facts. Consider rates of illicit drug use by race, despite how scapegoating blacks for drug use has driven the ‘war on drugs’:

‘Black youth are arrested for drug crimes at a rate ten times higher than that of whites. But new research shows that young African Americans are actually less likely to use drugs and less likely to develop substance use disorders, compared to whites, Native Americans, Hispanics and people of mixed race.’[21]

‘Contrary to popular assumption, at all three grade levels African American youth have substantially lower rates of use of most licit and illicit drugs than do Whites.’[22]

Yet the myth of black criminality still exists. Dylann Roof said to his nine African-American victims in Charleston, South Carolina just before he shot them, ‘I have to do it. You rape our women and you’re taking over this country.’[23] He had to attribute criminality to the black community to make them less than human, to justify his action to himself.

Aside from racial prejudice, it is impossible to explain why the federal mandatory minimum sentencing of crack cocaine offenses was set at 100 times that of powder cocaine. Predominantly black communities used crack. Predominantly white used powder. Scapegoating blacks continued to be the clear subtext. The result:

‘On average, under the 100:1 regime, African Americans served virtually as much time in prison for non-violent drug offenses as whites did for violent offenses.’[24]

The current law, as of 2010, makes the differential ‘only’ 18 to 1. We are by now painfully aware that many evangelicals, along with most of the U.S. population, embraced the ‘war on drugs’ for more than thirty years. Why did we do this? Why do some continue to?

Consider, too, the fact that most Americans still decline to call lynchings, other white-perpetrated violence against blacks, or white uprisings throughout U.S. history ‘domestic terrorism.’ On January 2, 2016, virtually no one called Ammon Bundy and his armed gang’s seizure of Oregon’s Malheur National Wildlife Refuge ‘domestic terrorism.’ But in 1985, when six adult black activists and five children ages 7 – 13 occupied a house in a black Philadelphia and caused public disorder, the organization MOVE was named a terrorist organization. Police bombed the house in short order, starting a fire that killed all six adults and five children, destroyed 65 houses in total, and left 250 people homeless.[25] Why the disparity in naming things what they are?

Once someone is placed into the ‘criminal’ category, a deeply retributive intuition kicks in.

‘White Americans who associate crime with blacks and Latinos are more likely to support punitive policies — including capital punishment and mandatory minimum sentencing — than whites with weaker racial associations of crime.’[26]

If your cousin steals from a store, and you like your cousin and think that this was just an error in his judgment, you probably believe that some consequences are in order. But you want those consequences to encourage your cousin’s rehabilitation and learning. You are more likely to plead with the storeowner to make your cousin pay him back, sweep and mop up the store, and then apologize personally to the storeowner’s family after hearing what the possible cost to them would have been. You’d want your cousin to learn something positive, and earn back trust and a place in the relational fabric of the community. In other words, the closer the person is to you, the more you opt for a restorative justice paradigm, not retributive.

But the more you distance yourself from him, and ‘criminalize’ the totality of his person, the more retributive your response will be. The notorious Stanford Prison Experiment by psychologist Philip Zimbardo also showed the power of scapegoating. The 2015 movie about the experiment shows the dynamics well. In the experiment, some students were asked to play guards and others were asked to play prisoners. Dr. Zimbardo played the warden, and didn’t hold ‘guards’ accountable for abusing ‘prisoners.’ The ‘guards’ started abusing the ‘prisoners.’ The experiment was called to an emergency halt, with alarming results.

Scapegoating the black community as criminal or morally inferior is quite similar. Often, there was (or is) no accountability for those who believed (or believe) in white supremacy and white innocence. No one pushed (or pushes) back against the myth of black criminality. So people simply believed (and still do believe) in the criminality of ‘the black other.’

If one’s doctrine of atonement is penal substitution, which elevates the principle of retributive justice, what might we want to consider? What is the social impact of nurturing in people the conviction that the atonement is about penal substitution?

The Christian denominations which were the most pro-slavery in the past and rooted demographically in the South – the Southern Baptist Convention[27] and the Presbyterian Church of America[28] – are also the ones most committed to penal substitutionary atonement today, and vocally so. While these two denominations have helpfully criticized their own history of support of slavery and segregation to some degree,[29] they also generously fund church planting efforts through The Gospel Coalition and other organizations, advocating penal substitutionary atonement as a core requirement, with money that has deep roots in slavery and segregation.

That last fact should give us pause. Southern Baptist historian Rev. Dr. A.L. Carpenter said, in his 2013 book Southern Baptists and Southern Slavery: The Forgotten Crime Against Humanity, that an unknown but substantial amount of ‘money came from the plantation owners, slave owners that built many churches in the South.’ Consequently, Carpenter writes:

‘It is the opinion of the author that every church built by the labor of the slave ought to be torn down, as every nail and plank must be odious to God!’[30]

One senses a troubled conscience across the Atlantic in Cambridge scholar Iain Whyte’s 2012 book Send Back the Money!: The Scottish Free Church and American Slavery. In American circles, Jennifer Oast explores this history in her 2010 article ‘The Worst Kind of Slavery: Slave-Owning Presbyterian Churches in Prince Edward, Virginia’ in The Journal of Southern History. Oast says:

‘Slavery was, however, so deeply embedded in Presbyterian culture in the American South by the antebellum period that it was very hard for churches to rid themselves of the practice. Slave ownership by congregations [not just individuals] was profitable; it paid the minister’s salary and provided for other needs of the church. In many cases the slaves were the only endowment the congregation required. This freed members from the necessity of making financial contributions to their church–a substantial benefit. Slaves were a good investment; they often improved on the original outlay through childbearing, so that in a few generations, a humble purchase of a handful of slaves might result in a substantial endowment of forty or fifty slaves. Congregational slave owning made all members of the church beneficiaries of slavery whether or not they owned slaves themselves or even approved of slavery.’[31]

Oast’s biography was not connected to the article so I am unsure of whether she represents a Presbyterian voice calling for some kind of denomination-wide self-examination, and I was not able to find any such statements in my online search.

These denominations were not trivial in terms of their impact on U.S. culture. Demographically, Presbyterians of all stripes were so numerous and influential throughout the 1800’s that non-Presbyterians feared that they would become a state church.[32] Southern Baptists began their denomination when over 365,000 Baptists withdrew from the national Baptist association, and the denomination continued to grow to become, at 15.5 members today, the second largest Christian body, next to the Catholic Church.[33] At the very least, an ethical appraisal of this church plant funding should be undertaken for its own sake, though that is not my purpose here. I want to examine what this strong advocacy of penal substitutionary atonement means. Does it need to be reconsidered, especially if it accompanies certain other theological ideas, which I will highlight below. What impact is this having on people? What impact could it have?

[1] Peter Holley and Sarah Larimer, ‘How America’s Dying White Supremacist Movement is Seizing on Donald Trump’s Appeal,’ Washington Post, December 21, 2015; https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2015/12/21/how-donald-trump-is-breathing-life-into-americas-dying-white-supremacist-movement/?hpid=hp_hp-top-table-main_trump_supremacist_11am:homepage/story; Evan Osnos, ‘The Far-Right Revivial: A Thirty-Year War?,’ The New Yorker, January 12, 2016; http://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/the-far-right-revival-a-thirty-year-war; Max Blau, ‘Still a Racist Nation: American Bigotry on Full Display at KKK Rally in South Carolina,’ UK Guardian, July 19, 2015; http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/jul/19/kkk-clashes-south-carolina-racism

[2] John Fea, ‘Ted Cruz’s Campaign Is Fueled By a Dominionist Vision for America,’ Religion News Service, February 4, 2016; http://www.religionnews.com/2016/02/04/ted-cruzs-campaign-fueled-dominionist-vision-america-commentary/

[3] Bryan Brunati, ‘Here are the Smartest and Dumbest States in America,’ Mandatory, November 17, 2015; http://www.mandatory.com/2015/11/17/here-are-the-smartest-and-dumbest-states-in-america/

[4] Matthew Pulver, ‘The South’s Victim Complex: How Right Wing Paranoia Is Driving a New Wave of Radicals,’ Salon, September 30, 2014

[5] Washington Post Editorial Board, ‘How Texas is White-Washing Civil War History,’ Washington Post, Jul 6, 2015; https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/whitewashing-civil-war-history-for-young-minds/2015/07/06/1168226c-2415-11e5-b77f-eb13a215f593_story.html; Ellen Bresler Rockmore, ‘How Texas Teaches History,’ New York Times, Oct 21, 2015; http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/22/opinion/how-texas-teaches-history.html

[6] Catherine Rampell, ‘Liberal Intolerance is on the Rise on America’s College Campuses,’ Washington Post, February 11, 2016; https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/liberal-but-not-tolerant-on-the-nations-college-campuses/2016/02/11/0f79e8e8-d101-11e5-88cd-753e80cd29ad_story.html; Kevin Carey, ‘Academic Freedom Has Limits. Where They Are Isn’t Always Clear.’ Chronicle of Higher Education, January 15, 2016; http://chronicle.com/article/Academic-Freedom-Has-Limits/234925; Rachel Alexander, Suspicions Confirmed: Academia Shutting Out Conservative Professors,’ Town Hall, June 10, 2013 http://townhall.com/columnists/rachelalexander/2013/06/10/suspicions-confirmed-academia-shutting-out-conservative-professors-n1616406 commenting on Neil Gross, Why Are Professors Liberal and Why Do Conservatives Care? (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013)

[7] Robert Tracy McKenzie, ‘Exchanging One Myth for Another,’ Faith and History: Thinking Christianly About the American Past blog, July 15, 2015; https://faithandamericanhistory.wordpress.com/2015/07/15/exchanging-one-myth-for-another-our-one-sided-memories-of-the-civil-war/;

[8] Robert Tracy McKenzie, ‘Racism in the Civil-War North,’ Faith and History: Thinking Christianly About the American Past blog, July 18, 2015; https://faithandamericanhistory.wordpress.com/2015/07/18/racism-in-the-civil-war-north/ (italics mine)

[9] Amy Goodman, ‘Ebony and Ivy: The Secret History of How Slavery Helped Build America’s Elite Colleges,’ Democracy Now!, November 29, 2013; http://www.democracynow.org/2013/11/29/ebony_and_ivy_the_secret_history reviewing Craig Steven Wilder, Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2013)

[10] Elias Isquith, ‘Gerald Horne on the Real Story of American Independence,’ Salon, May 30, 2014; http://www.salon.com/2014/05/30/white_supremacy_and_slavery_gerald_horne_on_the_real_story_of_american_independence/

[11] Amazon summary of Gerald Horne, The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America; http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1479893404?keywords=gerald%20horne&qid=1454962886&ref_=sr_1_2&sr=8-2

[12] Rodney Stark, The Victory of Reason: How Christianity Led to Freedom, Capitalism, and Western Success (New York: Random House, 2005), p.28, and my research http://nagasawafamily.org/article-slavery-and-christianity-1st-to-15th-centuries.pdf

[13] Mark Noll, The Civil War as a Theological Crisis (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), p.115 – 116

[14] Ibid p.125

[15] Peter H. Wood, ‘The Birth of Race-Based Slavery,’ Slate, May 19, 2015; http://www.slate.com/articles/life/the_history_of_american_slavery/2015/05/why_america_adopted_race_based_slavery.html ; although Winthrop D. Jordan, White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550 – 1812 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2012) argues that slavery and racism evolved together. He notes that the English in particular connected black skin with impurity, viewed African people as uncivilized and unchristian. However, by that time, long-standing English law and tradition forbade the enslavement of a fellow Christian and fellow Englishman.

[16] Kaia Stern, Voices from American Prisons: Hope, Education, and Healing (New York: Routledge, 2015), p.46

[17] Drug Policy Alliance, “A Brief History of the Drug War,” http://www.drugpolicy.org/new-solutions-drug-policy/brief-history-drug-war, notes,

‘The first anti-opium laws in the 1870s were directed at Chinese immigrants. The first anti-cocaine laws, in the South in the early 1900s, were directed at black men. The first anti-marijuana laws, in the Midwest and the Southwest in the 1910s and 20s, were directed at Mexican migrants and Mexican Americans. Today, Latino and especially black communities are still subject to wildly disproportionate drug enforcement and sentencing practices.’

[18] The Sentencing Project, Race and Punishment: Racial Perceptions of Crime and Support for Punitive Policies, 2014, p.3; http://www.sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/rd_Race_and_Punishment.pdf

[19] Ibid, p.3

[20] Charles M. Blow, “Crime, Bias, and Statistics,” New York Times, September 7, 2014; citing The Sentencing Project, Race and Punishment: Racial Perceptions of Crime and Support for Punitive Policies, 2014. See also Katheryn Russell-Brown, The Color of Crime: Racial Hoaxes, White Fear, Black Protectionism, Police Harassment, and Other Macroaggressions, 2nd edition (New York: NYU Press, 2008); also supported by Ted Chiricos, Kelly Welch, Marc Gertz, “Racial Typification of Crime and Support for Punitive Measures,” Criminology Volume 42, Number 2, 2004; http://www.uakron.edu/centers/conflict/docs/Chiricos.pdf;

‘This paper assesses whether support for harsh punitive policies towards crime is related to the racial typification of crime for a national random sample of households (N=885), surveyed in 2002. Results from OLS regression show that the racial typification of crime is a significant predictor of punitiveness, independent of the influence of racial prejudice, conservatism, crime salience, southern residence and other factors. This relationship is shown to be concentrated among whites who are either less prejudiced, not southern, conservative and for whom crime salience is low. The results broaden our understanding of the links between racial threat and social control, beyond those typically associated with racial composition of place. They also resonate important themes in what some have termed modern racism and what others have described as the politics of exclusion.’

[21] Maia Szalavitz, “Study: Whites More Likely to Abuse Drugs Than Blacks,” Time, November 7, 2011

[22] Monitoring the Future Survey, 2004, cited by Van Jones, “ARE Blacks a Criminal Race? Surprising Statistics,” Huffington Post, May 25, 2011

[23] Raf Sanchez, Peter Foster, ‘‘You rape our women and are taking over our country,’ Charleston church gunman told black victims,’ The Telegraph, June 18, 2015; http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/northamerica/usa/11684957/You-rape-our-women-and-are-taking-over-our-country-Charleston-church-gunman-told-black-victims.html

[24] American Civil Liberties Union, Fair Sentencing Act; https://www.aclu.org/node/17576

[25] Jeanette Woods, ‘Philadelphia Marks 30th Anniversary of MOVE Bombing,’ National Public Radio, May 13, 2015; http://www.npr.org/2015/05/13/406505210/philadelphia-marks-30th-anniversary-of-move-bombing

[26] Ibid, p.3

[27] The Southern Baptist Convention was formed in 1845 as a response to the Baptist Home Mission Society announcing that a Christian could not be a missionary and also hold slaves. The SBC fully supported slavery. They formally renounced this position on slavery and segregation in 1995 (http://www.sbc.net/resolutions/899).

[28] Prior to 1861, most Southern Presbyterians joined the ‘Old School’ in the ‘Old School – New School Controversy’ which was about how much Arminian teaching could be admitted to soften the traditional Calvinism. Many ‘New School’ Presbyterians who were in favor of this softening also supported abolitionism. The Civil War precipitated the withdrawal from the PCUSA General Assembly of what became the Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America. After the Civil War, it changed its name to the Presbyterian Church in the U.S. (PCUS). It existed as such from 1861 to 1983. In 1983, it merged with the United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America to form the Presbyterian Church of America (PCA). The PCA officially repented of racism in 2004, noting that internal racist elements still existed but were being held accountable. See Sonia Scherr, ‘A Denomination Confronts Its Past,’ Southern Poverty Law Center, May 31, 2010; https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2010/denomination-confronts-its-past

[29] Alan Cross, ‘Southern Baptists Have a History Problem: Let’s Stop Saying We Started Over Missions,’ SBC Voices, February 12, 2015; http://sbcvoices.com/southern-baptists-have-a-history-problem-lets-stop-saying-we-started-over-missions/

[30] Rev. Dr. A.L. Carpenter, Southern Baptists and Southern Slavery: The Forgotten Crime Against Humanity (Amazon Digital Services, 2013), p.21

[31] Jennifer Oast, ‘“The Worst Kind of Slavery”: Slave-Owning Presbyterian Churches in Prince Edward County, Virginia,’ The Journal of Southern History, November 2010; https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-242380089/the-worst-kind-of-slavery-slave-owning-presbyterian

[32] Bradley J. Longfield, Presbyterians and American Culture: A History (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2013)

[33] Robert A. Baker, ‘Southern Baptist Beginnings,’ The Baptist History and Heritage Society, 1979; http://www.baptisthistory.org/sbaptistbeginnings.htm notes,

‘The growth of the constituency of the Convention between 1845 and 1891 was substantial. From 365,346 members in 4,395 churches in 1845, Convention affiliation increased to 1,282,220 members in 16,654 churches by 1891. Scores of new ministries had been undertaken by the Convention, and a developing denominational unity gave the promise of effective cooperation through the years ahead.’

See also Eileen Lindner, editor, Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches (2010), p.11