Atonement Theories & Anger, Part 2: Jesus’ Anger

Mako A. Nagasawa

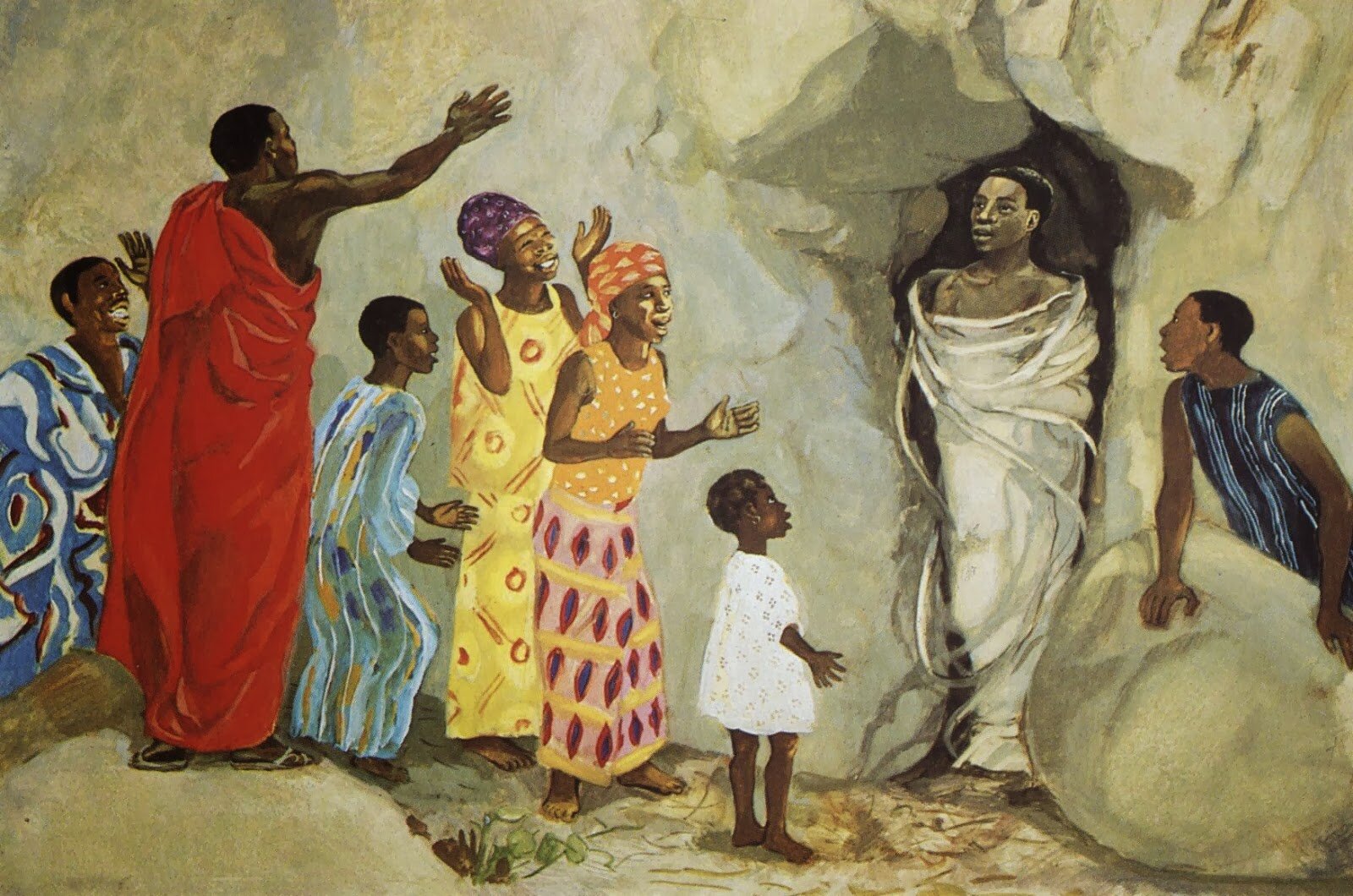

Jesus raising Lazarus from the grave. I found this on Till Christ Is Formed, the blog site of Catholic priest, Peter Kim Se Mang, SJ.

A Key Story: Jesus’ Anger by the Tomb of Lazarus

When Jesus stood by the tomb of his young friend Lazarus of Bethany, he expressed an emotion denoted by a word also used to describe horses snorting in anger: ἐνεβριμήσατο [enebrimēsato] (Jn.11:33, 38). Horses snort when they are afraid, alarmed, or upset. They snort when they see something they don’t know. They become tense and alert. For this word to be used for a human being, least of all Jesus, is striking. Some well-used Bible translations use vague language to blunt the force of this word.

● NASB says simply, “He was deeply moved.”

● CEB says, “He was deeply disturbed.”

● ESV adds the detail, “He was deeply moved in his spirit.”

● NRSV says, “He was greatly disturbed in spirit.”

● KJV and ASV say, “He groaned in the spirit.”

Other translations, however, do a better job conveying how upset Jesus was:

● The Message says, “A deep anger welled up within him.”

● NLT adds to that, “and he was deeply troubled.”

● CEV says, “He was terribly upset.”

● JUB offers, “He became enraged in the Spirit and stirred himself up.”

Reformed theologian B.B. Warfield agreed that Jesus “raged in spirit” and even said that his “fury was markedly restrained: its manifestation fell far short of its real intensity.” That is, what Jesus expressed outwardly was nothing compared to what he felt inwardly! Warfield says this emotion was “a profound agitation of his whole being.”[1]

Why was Jesus so angry? Against who? Or what? Understanding this story will help us explore the larger category of atonement, but I will approach it first as a reader of the story.

Although we can certainly be angry at circumstances that are not really anyone’s fault – like traffic on the road, a bike tire going flat, or a tree falling – that type of anger is hardly ever as intense as what Jesus seems to have felt. As human beings, if we are “terribly upset,” “enraged,” or “furious,” we are usually mad at specific people for doing something wrong. Was Jesus mad at someone? Mary? Now, I’ve met a few people and read an author or two who think that Jesus was angry at Mary, more or less, for misunderstanding him or doubting him. Their reason for thinking this is that Mary said the same exact words that Martha did just before: “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died” (John 11:21 and 32). Alternatively, they think Jesus was emotionally exhausted by having Martha and Mary question him in rapid succession, and the other folks at Bethany weeping (John 11:33) – a theory which I think very unlikely, if not impossible. What makes Jesus so angry at Bethany when Nazareth tried to kill him, and he walked away in a standoff, without Luke so much as mentioning an emotion (Luke 4:14 – 30)?

Most importantly, the two sisters differed sharply, and Jesus’ different responses to them indicate that. Martha was the sister who operated more “pragmatically,” as she showed her “hostess” sensibilities in an earlier episode (Luke 10:38 – 42). After Lazarus died and Jesus arrived at Bethany, Martha indirectly told Jesus – pragmatically – that she wanted him to do the miracle of raising her brother (John 11:22). Even though when Jesus pressed her, Martha backpedaled to the safety of the general Jewish hope of resurrection at the turning of the ages (John 11:24), this does not take away from the fact that Martha was talking to Jesus about his miraculous power. Mary, by contrast, was not.

Mary questioned Jesus’ delayed arrival, which seems to be why the narration includes those details about Jesus’ delay (John 11:6; 17). She was grieved that Lazarus had to experience death at all. Perhaps Lazarus’ passing was painful for him.

Also, Mary was probably suffering from trauma already. African American therapist Resmaa Menakem speaks of how the human body can retain the memory of trauma,[2] and also be impacted by the physical trauma of our ancestors, epigenetically.[3] Mary’s weeping at her brother’s death might indicate that she was impacted by stress in an unusual way. For hundreds of years, the people of Israel had been taken over by brutal empires in succession.[4] She might have seen Jewish men splayed on Roman crosses before. Jewish uprisings and skirmishes had happened in her lifetime. One that happened shortly before her birth was the failed revolt of Judas the Galilean.[5] Judas was a “failed messiah.” Around 6 AD, he and a Pharisee named Zadok led their followers to resist the Roman census. Judas proclaimed the Jewish state as a republic with God alone as king and ruler. He burned the houses and stole the cattle of some Jews who did report in the Roman census. Revolts continued to spread, and in some places serious conflicts ensued.[6] Under tremendous pressures like this, hurt people hurt people. The Roman Empire retaliated by publicly crucifying two thousand of the Jewish zealots, displaying them publicly as part of their social media campaign to intimidate anyone else who even thought about following that path. The uprisings continued, though. Jesus mentions a massacre of Galilean Jews in Jerusalem ordered by Pontius Pilate (Luke 13:1 - 2). And two weeks after this incident in John 11, Jesus would be crucified between two more failed revolutionaries, and his life would be traded for a third, a man named Barabbas. If Mary had seen such victims of violence, she probably would have felt a tightness in her chest, a sickness to her stomach, and other physical stress symptoms that people today feel when they watch a video of police beating or shooting ordinary citizens. When her brother Lazarus died, Mary might have re-experienced some of those feelings and bodily stresses.

Mary wondered whether Jesus loved Lazarus as much as she did. This is why, even though Mary said the same thing Martha did – “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died” – we can discern that she meant it in a very different way. John the narrator was unusually interested in this pattern of words having more than one meaning. It occurs multiple times throughout the narrative of John’s Gospel. It was essential to the way Jesus spoke, and the way people heard his words. On this occasion, Martha and Mary said the same thing, but were asking different implied questions. Both questions – one about Jesus’ power and one about his love – are questions we ask. Both questions are important in the face of human mortality and sin.

Was Jesus angry at Mary for questioning his love? If so, then should those of us who are “extra-spiritual” become “enraged” at people who weep at funerals as they wrestle with God’s love? What if Jesus had verbalized to Mary, “Well, Mary, I don’t see why you’re so upset. In fact, I’m the one who is upset. Because you should just believe in me. Your emotions insult me. And I’m sick and tired of being underestimated and disbelieved.” This moment was “about Mary.” Did Jesus suddenly make it “about himself”? We would call that cruel and even narcissistic, and rightly so.

Jesus’ Human Response to Mary as the Best Possible Response to Mary

Did Jesus simply empathize with Mary? The apostle Paul commanded that we be empathetic when he said, “Rejoice with them that do rejoice, and weep with them that weep” (Romans 12:15). It would be very strange if Jesus had no empathy, and only treated emotions as things to correct. In Scripture, the ideal is to have healthy and appropriate emotions, including emotions that are responsive to others. It would not be loving to walk happily along, meet a friend in grief, and not be emotionally moved at all. Can you imagine what the implications would be for us if Jesus had said to Mary instead, “No matter what you’re feeling, I feel happy! Oh so happy! Because I know the Father loves me. I have the “eternal perspective.” Why don’t you just feel what I feel?”

Of course Jesus empathized with Mary, since she was grieving her brother’s death. Jesus did not, however, do with Mary what I tend to do in my more empathetic moments: draw from my own experiences of loss. I think it is likely that Jesus was thinking about other people besides Lazarus, too. But fundamentally, Jesus was present in that very moment to Mary in her pain, and present to Lazarus’ physical and emotional absence. Not for nothing did Mary and Martha tell Jesus that Lazarus was sick by calling their brother “he whom you love” (John 11:3) at the start of this story. The Jews observing Jesus weep at Lazarus’ tomb said in wonder, “See how He loved him!” (John 11:36) They were not mistaken. Jesus’ anger and grief were for Lazarus and Mary personally, because he knew them, and loved them. His fury and tears were not from his memory of others, or his experience from elsewhere, as if Jesus was showing Mary that he had once felt loss, too. His trembling anger was not in parallel with Mary, outwardly similar but inwardly different. He felt Mary’s specific anger and grief, and touched it, commingling himself with it. Jesus came to stand with us in the same love we bear for others. He bore it, too. And he surpassed it.

Jesus’ anger was aligned with Mary’s and went beyond Mary’s, because his love for Lazarus went beyond hers. When Jesus showed his love for Lazarus – when he allowed tears to fall from his eyes, snot to run from his nose, and his chest to be gripped by sobs – he also showed his love for Mary. Jesus was not there to remain placidly calm while saying a few words. In fact, he said no words to Mary. Jesus was there to be furious, to grieve, to bear the emotional brunt of Lazarus’ death with her. Jesus stood with her to shout from earth to the heavens in a prayer of protest.

As Jesus went deeper and more precisely than Mary in her anger, he also became louder than Mary. Jesus “covered” Mary in her anger and sorrow. In Jewish culture at the time, the grieving family at a funeral would hire professional mourners. They would wail loudly to “cover” the wailing of those who were smitten more personally. This was not meant to be insincere, although it may sound that way to us today who prize “personal authenticity.” In a small village, with tight social networks, these professional mourners probably knew Lazarus, too. They probably felt genuinely sad, just not to the same degree as Lazarus’ family. These mourners afforded Mary sound and space: sound to know she was not alone, and space to raise her voice accompanied by those of others as a protest to the heavens. Jesus joined those mourners, and eclipsed them all. He was not keeping himself composed because he had words to say, like how I might feel at a funeral. The response Mary demanded from Jesus was not one of words, but a demonstration of emotional solidarity, going from earth to heaven.

And Jesus also showed an emotional solidarity coming from heaven to earth, which I will explore in the next post.

Questions for Reflection

● How does Jesus’ response to Mary show his empathy?

● How does Jesus’ response to Mary show more than our typical human empathy?

● What if our empathy for others had the type of precision and depth that Jesus showed here?

Mary’s Response to Jesus as the Best Possible Response to Jesus

Mary of Bethany had sat at Jesus’ feet along with the male disciples to learn, which was not what women typically did in Jewish rabbis’ circles, but Jesus had welcomed her and other women (Luke 10:39). Not long after Jesus raised Lazarus from the tomb, Mary anointed Jesus’ feet with expensive perfume for his burial, which she did as a prophetic act because she understood that Jesus would give up his life, die, and be buried. The other disciples did not yet understand that (John 12:3, 7). But Mary did.

Jesus’ self-disclosure of his emotion with Mary suggests much about the role of discernment. Jesus discerned that Mary was ready to feel the emotional force of his anger and tears, not just know things about him in words, important as that is. Those are two different things, especially with anger and grief. God will often place us in situations where we need to moderate ourselves emotionally because our audience includes children, or people who are simply uninformed, or people who are defensive, not ready to look seriously at how they have been part of ongoing human evil and injustice. There are good reasons why our discernment is always important. For Jesus, emotional self-expression was not a higher value than love for a neighbor. He did what he discerned was appropriate for Mary.

By extension, the dynamic between Jesus and Mary helps remind me that sometimes, people showing their anger in my presence was an act of vulnerability and trust, and vice versa. They entrust me with the knowledge of themselves, like Jesus entrusted Mary.

That was very often true of my friends who are working class and felt taken for granted during the COVID-19 pandemic, after already long struggles for more wages, safer workplaces, and fairer treatment. They shared their anger with me. Sharing in other settings in corporate America was not always understood, or welcome.

Or, some of my friends who are black and brown entrusted me with their anger and grief about racism in America. For them, it is often safer to not share. Some had shared their feelings and found that information turned against them. They were stereotyped as the “angry black man” or the “angry black woman.” That can be career-limiting around certain people.

Or, sometimes people become more aware of repressed emotions about their families of origin. When we are children, our needs for attachment and stability are stronger than our need to discern the precise truth about how we are being treated. Anger is an important step, not only in the process of emotional healing, but also in the growth of moral and relational discernment. Sometimes, our parents are not willing to hear about how we experienced them, so we have to process our emotions and memories with others. Sometimes, anger is the result of experiencing Sabbath rest in some way, as people no longer have to fight to survive, but can pause, rest, and reflect. Sometimes, anger represents them clawing back hope from a defeated, nihilistic place. It is a positive step in a long journey. Anger is often an expression of hopes being re-nurtured, or love realizing what was frustrating it.

Mary’s believing pathos drew forth a response from Jesus along the lines of deepened communion, and Mary was able to hear and see in Jesus’ deep pathos his deeper love. It was almost certainly Jesus’ deep anger and grief that showed Mary what Jesus would soon endure himself (12:3, 7). If Jesus felt this deeply about human death and the sin that made it necessary — because God had exiled humanity from the tree of life so that we would not eat from it while in a corrupted state, and thus immortalize human evil straightaway — then this could mean only one thing. Jesus would go fight death in its own domain, on our behalf. For he had already come to fight sin in its domain on our behalf, in the domain of the human. He was the “Word become flesh” (1:14), come to set free humanity from the bondage of the corruption of sin – first his own humanity, then that of all who believed in him.

So when I encounter someone who is angry about mistreatment, injustice, and evil, I take that as a personal invitation to get to know that person, and even through that person, to get to know Jesus just a little better. For Jesus is angry about mistreatment, injustice, and evil, traced back into the corruption of sin. Jesus will lead me to also “be angry” (Ephesians 4:26) in a way that transitions to mourning and grief (Matthew 5:4), and eventually, to act out of love for God and neighbor in partnership with the Spirit of Christ.

Sometimes, people’s understandings can change, and their emotions do change. But the emotional sharing itself can still be a gift because it is part of an honest process. And especially when people’s understandings are accurate, and the people with whom they are angry do not listen, emotional communion is vital. Of course, it helps to be aware of emotionally manipulative people, but that is not who Mary was. Like Mary sharing with Jesus, and Jesus sharing with Mary, other people sharing their anger and tears is a gift of trust.

To reinforce this point about Mary’s faith, Jesus seems to have seen something special about her cry and this moment. Why would I say that? Because at other funerals, Jesus seems to have chosen not to reveal this depth of emotion. At the funeral procession of the son of the widow of Nain, he did not show this anger and grief (Luke 7:11 – 17). Some people criticized Jesus, saying, “You did not mourn,” when they sang a “song of mourning” (Matthew 11:16 – 19), presumably at funerals, because this particular question was not being put to him. If so, then Jesus’ demonstration of his depth of feeling for Lazarus, in solidarity with Mary, might have been unusual for him. Mary showed every indication in Scripture of having spiritual insight and devotion to Jesus, and Jesus said that such “belief” – a major theme in John’s Gospel – is answered by his friendship, trust, and self-revelation (cf. John 15:12 – 15).

We need to explore Mary’s place in the story because “belief” is such a prominent theme in John’s Gospel, and Mary is a high point in the story. The prologue (John 1:1 – 18) indicates that God provides witnesses, beginning with John the Baptist, “so that all might believe through him” (1:7). The result of believing in Jesus’ name is being united with the Son by the Spirit and inheriting the Son’s relationship with his Father: “But as many as received him, to them God gave the right to become children of God, to those who believe in his name” (1:12). Nathanael was first to believe in Jesus in some limited and preliminary sense (1:50), based on what he understood from “Moses and the prophets” (1:45), and Jesus’ reply was to promise Nathanael that he will see “greater things” of the type of movement between earth and heaven centered on Jesus himself as the Son of Man (1:50 – 51). After the wedding of Cana, where Jesus turned water into wine, “his disciples believed in him,” in some preliminary way (2:11). Through the narrative, John indicates that “believing” in Jesus can grow higher and reach deeper into the Scriptures, the more one spends time with Jesus (2:22).

This pattern continues all the way to the empty tomb, when “the younger disciple” enters the tomb after Simon Peter “and he saw and believed” (20:8). But it was not yet from the Scriptures that they believed or coordinated the meaning of Jesus’ bodily resurrection (20:9). Thomas is the high point along this theme. Famously, Thomas said that unless he saw and touched the scars on Jesus’ body, “I will not believe.” However, Thomas saw the resurrected Jesus but did not touch him, and yet believed, which prompted Jesus to look ahead and remark, “Blessed are those who did not see, and yet believed” (20:29). John reminds his readers in one of his closing statements that he wrote “so that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing, you may have life in his name” (20:31).

Believing is a critical element of all the miracle stories, and Jesus’ raising of Lazarus is the greatest of the miracles. Of the seven miracles in John’s Gospel (2:1 – 12; 4:43 – 54; 5:1 – 15; 6:1 – 14; 6:16 – 20; 9:1 – 41; 11:1 – 44), this one is the seventh. Mary’s belief, correspondingly, is the greatest to that point. With Martha, Jesus reconfigured the traditional Jewish belief in resurrection and centered it around himself. “I am the resurrection and the life,” Jesus said, and summoned Martha to believe: “Do you believe this?” (11:25 – 26) She confessed that she had “come to believe that you are the Christ, the Son of God, he who comes into the world” (11:27). Jesus’ conversation with Martha suggests that he discussed with Martha what he knew she needed: to grow in understanding him, to center the traditional Jewish hope of resurrection upon and within his person, and whether she would continue to grow in believing him.

Jesus’ different responses to the two sisters now becomes more intriguing and important. Jesus did not have a conversation with Mary because he did not need to. She already believed these things about him. Instead, Mary was struggling emotionally with something else: Jesus’ delay and what that might have meant about Jesus’ love for Lazarus and her. Mary’s implied question was virtually identical with the cry, “How long, oh Lord,” from the Psalms (e.g. Psalm 6:3; 13:1; 94:3). It was not the cry of someone who thought that God might not exist because of human evil and suffering, a position that is self-defeating because it reduces evil to one’s opinion and suffering to the processes of nature. Mary’s cry was the cry of a person who trusted Jesus, who understood him, and therefore called out to Jesus, believing.

In response to Mary’s belief in him, Jesus entrusted her – and those around her – with one of the most profound displays of his human emotion recorded anywhere. This human emotion of anger and grief reflects the “divine emotion” as best we can understand it. The onlookers marveled, wondering at how much Jesus loved Lazarus (11:36). That was Jesus’ answer to Mary.

If the Son fully reveals the Father, then this means a great deal for how we interpret the anger of God. And if the Son fully reveals what it means to be truly human, then this means a great deal for whether we participate by the Spirit in Jesus’ humanity, and his human emotion. We turn to that in the next post.

Questions for Reflection

● How might sharing and showing anger be an act of trust?

● If someone else shares their anger – even if that person is angry with you, which can be unsettling and uncomfortable – how can you receive it as an act of trust on their part?

● If you are someone who wants to rush through anger – whether it’s your own or someone else’s – what might you miss?

● What if our empathy for others had the type of discernment that Jesus showed here?

[1] B.B. Warfield, “The Emotional Life of Our Lord,” found here: http://www.monergism.com/thethreshold/articles/onsite/emotionallife.html. Excerpted from B.B. Warfield, The Person and Work of Christ (The Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company, 1989) p.93 - 145.

[2] Resmaa Menakem, My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies (Central Recovery Press: Las Vegas, NV, 2017), p.187 - 197.

[3] Ibid p.37 - 55.

[4] The Assyrian Empire had taken over the Northern Kingdom of Israel in 721 BC. The Babylonian Empire had taken over the Southern Kingdom of Judah in 586 BC. From there, Persia, then Greece, then Rome had taken over.

[5] Luke records Rabbi Gamaliel’s mention of this uprising in Acts 5:37. Josephus, Wars of the Jews 2.118 calls the uprising the most serious incident between Pompey’s conquest of Palestine in 63 BC and the fall of Jerusalem in 70 AD.

[6] N.T. Wright, The New Testament and the People of God (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1992), p.180.