Isaiah 53, Part 3: Isaiah and the Sacrificial System

Isaiah’s Understanding of Israel’s Sacrificial Animals

52:15 Thus he will sprinkle many nations…

53:10 …But the LORD was pleased to crush him, putting him to grief;

if he would render himself as a guilt offering…

Reference to sprinkling and sacrificial animals like a lamb or sheep (Isa.53:7) takes us deep into the heart of Israel’s sacrificial system (which I’ve written about here and also in connection with circumcision here). Isaiah describes the Messiah as a sin/guilt offering (Isa.53:10). Those offerings involved the sprinkling of blood, as described in Leviticus 4 – 5. The fact that (1) Isaiah 52:13 – 53:12 can be perceived as chiastic, and the fact that (2) the sin/guilt offering is mentioned in section A’ as a development of the ‘sprinkling’ mentioned in section A, are significant in understanding Isaiah’s arrangement of his poetic material.

The Structure of Isaiah 52:13 – 53:12

A. The Servant Reigns and Cleanses Others (52:13 – 15)

— B. The Servant Suffers Without Praise (53:1 – 3)

— — X. The Servant Suffers to Heal Us (53:4 – 6)

— B’. The Servant Suffers Without Guilt (53:7 – 9)

A’. The Servant Reigns and Gives Life to Others (53:10 – 12)

Purification or Punishment?

How did Isaiah understand the animal sacrifices? Interestingly, the Greek Septuagint (LXX) translation of Isaiah 53:10 reads:

And the Lord desired to purify/cleanse him from his wound

By comparison, the Masoretic text (the Hebrew text of the Masoretic Jewish community between the 7th to 10th centuries AD) reads:

NIV: Yet it was the Lord’s will to crush him and cause him to suffer, and though the Lord makes his life an offering for sin

NASB: But the Lord was pleased to crush Him, putting Him to grief; if He would render Himself as a guilt offering

NKJV: Yet it pleased the Lord to bruise Him; He has put Him to grief. When You make His soul an offering for sin

NRSV: Yet it was the will of the Lord to crush him with pain [or by disease; meaning of Hebrew uncertain]. When you make his life an offering for sin [meaning of Hebrew uncertain]

The Difference Between Manuscripts

The difference between the LXX and the Masoretic text on Isaiah 53 has generated much discussion.[1] Suffice to say that the manuscript difference could be significant because Matthew quotes from the LXX version of Isaiah 53:4 in Matthew 8:17. That fact by itself weakens the case for penal substitution just a bit. If the Hebrew text of Isaiah 53:10 standing behind the LXX was the more accurate version, the case for penal substitution is further weakened. For to speak of the Messiah himself being purified or cleansed leads us very naturally into the ontological-medical substitution atonement theory. The NRSV’s acknowledgements about the uncertainty in Isaiah 53:10 reflect that possibility. The NRSV’s acknowledgement that Isaiah 53:10 can be translated ‘crush him by disease’ is significant to determining what Isaiah’s understanding of ‘sin offerings’ were.

Who Used Septuagint Isaiah? The Apostle Paul

It is also quite significant that Paul in Romans 11:26 follows the LXX of Isaiah 59:20. The Redeemer will, according to this manuscript family, come to

‘turn transgression from Jacob.’

Paul does not quote from the (proto?) Masoretic Text which refers to the Redeemer who will come to

‘those who turn from transgression in Jacob.’[2]

That is quite a subtle but significant theological difference. Add to this the fact that Paul deliberately chooses to quote exclusively from the LXX version of Isaiah throughout Romans 9 – 11, a section where he considers Isaianic material in dense frequency.

Romans | Isaiah | LXX or MT

Romans 9:27 – 28 | Isaiah 10:22 – 23 | LXX

Romans 9:29 | Isaiah 1:9 | LXX

Romans 9:32 – 33 | Isaiah 8:14; 28:16 | LXX/MT

Romans 10:11 | Isaiah 28:16 | LXX

Romans 10:15 | Isaiah 52:7 | LXX/MT

Romans 10:16 | Isaiah 53:1 | LXX

Romans 10:20 – 21 | Isaiah 65:1 – 2 | LXX

Romans 11:8 | Isaiah 6:9 – 10; 29:10 | LXX/MT

Romans 11:26 – 27 | Isaiah 59:20 – 21 | LXX

Romans 11:27 | Isaiah 27:9 | LXX

Romans 11:33 – 34 | Isaiah 40:13 | LXX

(Paul quotes from LXX Isaiah whenever he quotes Isaiah.) Even when no discernable theological difference appears between the Greek LXX and Hebrew Masoretic, it would appear that Paul prefers the LXX version of the Suffering Servant Song in Isaiah 52:13 – 53:12. And in the case where a discernable theological difference does occur, at Isaiah 59:20, Paul indicates his preference for the LXX. From all indications, Paul would have also preferred the LXX variant of Isaiah 53:10.

Who Used Septuagint Isaiah? The Early Church

Furthermore, early church theologians preferred the LXX version of Isaiah 53:10. It is cited by Clement of Rome, Epistle to the Corinthians, chapter 16. Justin Martyr cited it in two places: First Apology, chapter 51, and Dialogue with Trypho, chapter 13. Athanasius of Alexandria cited it in On the Incarnation 34.3. Augustine quoted it in Harmony of the Gospels, book 1, paragraph 47. John Chrysostom cited it in Homilies on First Corinthians, Homily 38, regarding 1 Cor.15:4.

The great 3rd century biblical commentator Origen of Alexandria also preferred to quote LXX Isaiah (Commentary on the Gospel of John, book 6, paragraph 35 quotes LXX Isaiah 53:7; Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, book 12, chapters 29 – 32 quotes LXX Isaiah 53:2 – 4). Origen’s preference for LXX Isaiah is suggestive, since he wrote the monumental Hexapla, a 28 year project where he did word-for-word comparisons of six versions of the Hebrew Bible including one Hebrew version, the Greek LXX, and other Greek translations.

This preference for LXX Isaiah 53:10, and LXX Isaiah generally, by ancient authorities is weighty. The early church held to the medical substitution view of atonement, as I have shown here. Despite the efforts of some penal substitution supporters to suggest otherwise, the early church did not hold to penal substitution, and this preference for the LXX version of Isaiah 53:10 reinforces the historical assessment.

However, the Dead Sea Scrolls (1QIsaa) version of Isaiah 53:10 agrees with the Masoretic Text, so we cannot categorically say with confidence that the LXX reflects the correct Hebrew text here. For the sake of discussion, therefore, I will not take the LXX as authoritative. I will instead consider the Masoretic text, and the larger framework of Israel’s sacrificial system.

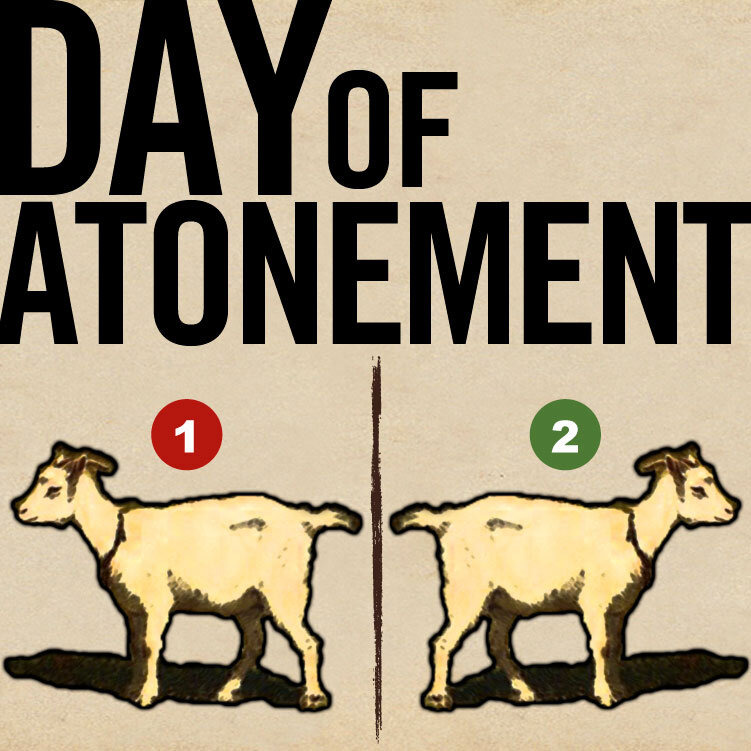

I am not choosing one manuscript over the other here. Instead, I am exploring why both manuscript variants are explicable and unifiable based on Isaiah’s understanding of an earlier text: the Pentateuch’s story of the sacrifices and its annual calendar, a text about which there is no variation and no lexical range wide enough to be ambiguous. I believe that Isaiah saw the Servant-Messiah in terms of the sin-offering and the sin-bearer like the two goats of Yom Kippur.

God Was Acting Like a Dialysis Machine, Taking Impurities and Giving Back Purity

Through the sacrificial system involving animals, God was acting like a modern-day dialysis machine. I have given a much more thorough explanation and defense of that view in this post and in a longer essay.[3] In brief, through the sanctuary system, God summoned Israelites to give Him their impurity by laying their hands on an animal, slaying it, and sending that animal to Him for Him to symbolically consume, while He returned back to them His purity by giving Israel the uncorrupted blood of the animal. The Messiah is clearly put into the place of the sacrificial animal: a lamb, a sheep (Isa.53:7).

What were sin/guilt offerings? In Leviticus 4 – 5, the offering is referred to by both names, but it is one type of offering regardless of which name is used in translation. Whereas burnt offerings and peace offerings existed long before the sanctuary (Gen.4:3 – 4; 8:20 – 21) and mention of altars implies sacrifices (in Gen.12:7, 8; 13:18; 22:13; 26:25; 33:20; 35:1 – 7; Ex.17:15; 18:12; 24:4, 6 – 8), the sin/guilt offerings were added to the sanctuary system specifically because of the need to maintain the purity and holiness of the sanctuary. That included its furniture, its vessels, its gifts and offerings – in other words, non-human objects. Obviously, the sanctuary also promoted purity and holiness in the community at large.[4] Sin/guilt offerings were unique because of the blood sprinkling rite attached to them. The blood of innocent animals cleansed the things on which they were sprinkled. It was therefore an act of reconsecrating something for service after a human sin had been committed.

A priest who sinned had to reconsecrate the sanctuary objects that he regularly touched (Lev.4:5 – 7). If the whole congregation committed error, the priest needed to reconsecrate the sanctuary with innocent animal blood, too (Lev.4:13 – 18). If a leader of Israel unintentionally committed error, the sanctuary needed to be reconsecrated with innocent animal blood as well (Lev.4:22 – 25). If anyone of the common people unintentionally sinned and became aware of it, he or she needed to do the same (Lev.4:27 – 35). A person who was under court order to tell the truth as a witness but failed to (Lev.5:1), or a person who touched something or someone unclean (Lev.5:2 – 3), or a person who swore thoughtlessly and then recalled it (Lev.5:4 – 5) had to bring a sin/guilt offering to cleanse the altar of the sanctuary with innocent animal blood (Lev.5:6 – 9). The only case in which blood was not demanded in the sin offering was when the person was exceptionally poor and had to use fine flour (Lev.5:10 – 13).

The Difference Between the Animal’s Blood and Its Flesh

The priests were to avoid eating blood at all costs, since it represented the life of the animal (Lev.17:11), and the uncorrupted life-blood was God’s gift to Israel to provide a measure of life from God on behalf of Israel so they could live in the garden land (Mal.3:6 – 12). The uncorrupted animal blood served to buffer the presence of corrupted Israelites on the land, and perhaps also to mitigate the bloodshed committed by human beings akin to Cain’s slaying of Abel (Gen.4:1 – 16), which would have caused the garden land to become unfruitful for Israel.

Equally significant as the blood of the animal in the sin/guilt offering was its flesh. Yet the flesh of the sacrificial animals is strangely but frequently overlooked by those who study the sacrifices, by defenders and critics of penal substitution alike.[5] The priests were to eat some of the flesh of the sin offerings (Lev.6:24 – 30). This act was connected to the overall symbolism of eating, which represents internalization of the sin as it traveled from the people of Israel into the priests. Moses took this so seriously that he became angry with Aaron’s sons Eleazar and Ithamar for not eating the goat offered as a sin offering (Lev.10:16 – 18). As Moses queried Aaron, he made very explicit the connection between the priests eating the sin offering and atonement:

‘Why did you not eat the sin offering at the holy place? For it is most holy, and He gave it to you to bear away the guilt of the congregation, to make atonement for them before the LORD.’ (Leviticus 10:16; cf. Numbers 18:9 – 11)

This incident shows that the priests’ responsibility to eat the sin offering is of enormous significance to our understanding of atonement, especially in Isaiah who says that the Servant will ‘bear the sin’ of others. If the Israelite worshiper approached God in the sanctuary, there was a reciprocal eating. God would feed him a meal at His sanctuary, representing something of what humanity lost in Eden: the chance to eat with God. But God would also ‘eat’ the sin of the worshiper through His priests. In this way, the priests ‘bore the guilt in connection with the sanctuary’ and ‘in connection with [the] priesthood’ itself (Num.18:1).

Moreover, very unlike sin offerings on every other occasion, which were eaten by the priests (Lev.6:24 – 30; 10:16 – 18), on the Day of Atonement, the remains of the bull and the first goat were not to be eaten:

27 But the bull of the sin offering and the goat of the sin offering, whose blood was brought in to make atonement in the holy place, shall be taken outside the camp, and they shall burn their hides, their flesh, and their refuse in the fire. 28 Then the one who burns them shall wash his clothes and bathe his body with water, then afterward he shall come into the camp. (Leviticus 16:27 – 28)

Any valid treatment of Isaiah 53 and the Day of Atonement rite needs to account for this irregularity.[6] Normally, on all occasions except for the Day of Atonement, the priests would eat the flesh of the sin offering. It was a picture of the priests internalizing Israel’s sin, storing it up within themselves. Those remains were considered to be so holy that, unlike every other occasion when human contact with a dead animal was a bit circumspect, touching the flesh of the sin offering made the person ‘consecrated’ (Lev.6:27), which means, I presume, committed to the eating of the remains. This was a serious matter. Moses was quite angry with Aaron’s sons on the occasion when they did not eat the remains of the sin offerings (Lev.10:16 – 18). However, in the case of the Day of Atonement, the ritual law is very clear that absolutely no one was to eat the hides, flesh, or refuse of the bull or goat. That is, the sin was not to symbolically cycle back into the priests. The purpose and symbolism of the Day of Atonement absolutely requires that God consume all the sin (iniquity and uncleanness) of Israel, putting all of it to death by simultaneously consuming it within Himself by fire, and separating it from the people and priests through the scapegoat.

Isaiah’s Vision of the Messiah as Sin-Bearer

As J. Alan Groves points out, Isaiah describes the Suffering Servant using scapegoat language in the final stanza of the Servant Song.[7] ‘He will bear their iniquities’ (Isa.53:11) and ‘He himself bore the sin of many’ (Isa.53:12). The linguistic and conceptual ties are convincing. Because the scapegoat was said to ‘bear on itself all their iniquities to a solitary land’ (Lev.16:22), the sin-bearing of the Servant is undeniably a reference to the scapegoat, although the Servant is clearly human. So how did the scapegoat bear the sin of Israel originally? Through the death of the bull, the high priest offered atonement for himself on the Day of Atonement, and then through the death of the first goat, he appeared before God in the holy of holies so that God could symbolically receive the stored up uncleanness of the Israelites, eaten by all the priests in the sin offerings. The laying on of the high priest’s hands onto the scapegoat (Lev.16:21) appears to represent a symbolic transfer of some sort serving as a parallel image to the first goat. The scapegoat running off into the wilderness can be said to represent God separating our sinfulness from Israel by taking it into Himself, which is the only place for it to go. The scapegoat probably served as the poetic inspiration for saying, ‘As far as the east is from the west, so far has He removed our transgressions from us’ (Ps.103:12), and ‘You will cast all their sins into the depths of the sea’ (Mic.7:19).

The two goats of the Day of Atonement ritual simultaneously represent one action taken by God in connection with all the sin stored up by the priests. He takes sin into Himself to destroy it, simultaneously sending it away. With reference to Jesus and the Servant Song in Isaiah, the two goats refer not to the death of Jesus and his forsakenness from the presence of God, but to the death of Jesus as he killed the corruption in his human nature, and his sending the corruption of sin far, far away from both God and his human nature. In him, God consumed it. God condemned sin in the flesh of Christ (Rom.8:3). Within Jesus, therefore, who is the new temple of God, where God and human nature co-mingle in fully reconciled union, there is no more corruption of sin.

Importantly, the Epistle to the Hebrews also sees each of the two goats as foreshadowing Christ. Just as the first goat was slain by the high priest so he could enter the presence of God in the sanctuary, so Jesus entered the more perfect sanctuary through his own blood (Heb.9:11 – 12). Even the disposal of the bodies of the animals, including the first goat, outside the camp/city (Lev.16:27 – 28) is compared to Jesus’ suffering ‘outside the gate’ (Heb.13:11 – 13). And, just as the second goat, the scapegoat, was driven out into the wilderness to ‘bear the sins of many,’ so also Jesus was ‘offered once to bear the sins of many’ (Heb.9:27 – 28) in order to actually and ontologically ‘take away sins’ (Heb.10:4). Hence, the language of sin-offering and sacrifice in Scripture denotes God’s act of separating the corruption of sin from the human person. God was enacting medical symbolism in the sanctuary to eventually enact a medical reality in the body of Jesus. The modern dialysis machine is the best and most appropriate analogy to the sacrifices in the Old Testament. The animal sacrifices and blood atonement in the Old Testament did not represent a bloodthirsty God. They represented a blood-purifying and blood-donating God. Or, more precisely, a life-purifying and life-donating God. God was saying, and is saying, ‘Give me your impurity. I will give you back purity.’

Hence we must be careful to read Isaiah 53 with reference to the death of the Servant, not the torture or torment of the Servant. Since Jewish tradition requires the death of the animal be as painless as possible, as absolutely nothing in the Pentateuch suggests that the animal must suffer pain, close examination of the sacrificial system leans us towards the conviction that Jesus’ death is significant, not whatever Roman torture or hypothetical spiritual torment he suffered along the way. John Calvin’s theory that Jesus endured hell on the cross is completely unfounded, both in Scripture and in theological logic. In this case, as always, the antitype [Jesus] provides more clarity than the type [the scapegoat; the Servant prophecy].

The motif of blood sprinkling can be integrated carefully as well. In the Jewish sacrificial system, blood represented life (Lev.17:11). Animal life was not corrupted by sin; only human life was. Hence, symbolically, uncorrupted animal blood was a cleansing, life-giving agent. That Jewish memorial anticipated Jesus’ blood being cleansed by him. Jesus spiritually cleansed his own body and blood throughout his obedient life (Heb.5:7 – 9), death, and resurrection, and then become a sacramental reality, available for us to internalize by his word and Spirit (e.g. Jn.6:51 – 63). The Eucharistic communion elements of bread and wine thus serve as a reminder that Jesus – who carried the same sinful flesh that we have, resisted it, defeated it, and cleansed his humanity of it – is the nourishment from God which we must internalize by the Spirit. Jesus’ life now cleanses us by our participation in him and receiving him into ourselves. The sprinkling points to an ontological substitution, not a penal substitution.

This is why Isaiah sees the Messiah’s work as extending beyond Israel to all Gentile peoples of the world, the coastlands, the nations far away who will stream to him, etc. (Isa.2:1 – 4; 42:1 – 9; 60:1 – 16). He will ‘sprinkle many nations’ (Isa.52:15), in effect by his Spirit in connection with his life (blood), because his life (blood) has been cleansed of the impurity of iniquity. The Messiah will share in all the conditions of Israel’s exile, including her fallen, corrupted humanity. He himself will not sin, but he will bear sinfulness for others, consuming it, in order to extend his healing to them.

Conclusion

Once we understand the Pentateuch’s treatment of the sin/guilt offering and the sprinkling, we can see that Isaiah did not understand the Suffering Servant Messiah as a penal substitute for Israel. That is not what the sacrifices were, in particular, the sin/guilt offering of Leviticus 4 – 5 and the Day of Atonement offering of Leviticus 16. Isaiah’s Servant did not absorb a punishment that would have fallen on Israel to deflect it from them. Rather, he suffered a punishment with Israel and with humanity that Israel and humanity were already experiencing.

Jesus was a medical, or ontological, substitute for Israel and humanity. He was the doctor who became the patient to acquire the disease and defeat it, and develop the antibodies within himself. He did within himself what humanity could not do. He put to death the corruption of sin. He raised his humanity fresh and new, to offer himself to us by his Spirit. Hence Isaiah, after discussing the suffering and death of the Servant in the second, third, and fourth stanzas (Isa.53:1 – 3, 4 – 6, and 7 – 9) refers once again to the Servant’s resurrection and reign (Isa.53:10 – 12). Logically, the LXX version of Isa.53:10 makes more sense as a connecting thought from the fourth stanza to the fifth:

‘And the Lord desires to purify/cleanse him from his wound.’

Sharing in the death of humanity (if not our fallen human nature leading up to his death) can be considered a wound in Isaiah’s own terms. The fifth stanza emphasizes that Jesus ‘bore away’ the iniquity to share his inheritance with others (Isa.53:11, 12). That leads, later in Isaiah, to the crisp statement of medical substitution from the Greek Septuagint variant of Isaiah 59:20, quoted pointedly by Paul in Romans 11:26:

‘The Deliverer will come from Zion to turn transgression from Jacob.’

[1] William Bellinger, Jr., and William Farmer (editors), Jesus and the Suffering Servant: Isaiah 53 and Christian Origins (Norcross, GA: Trinity Press, 1998)

[2] Rikk Watts, ‘Isaiah in the New Testament’, edited by David G. Firth and H.G.M. Williamson, Interpreting Isaiah: Issues and Approaches (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2009), p. 225 – 226 says, ‘The two are not divergent views as different ways of expressing the same reality.’ However, while I agree that the reality contains both views, the LXX view that the Redeemer has come to turn transgression from Jacob is logically prior, is much closer to my analysis of Isaiah 53:11 – 12 and the scapegoat motif, and is attested by Paul’s quotation.

[3] Mako A. Nagasawa, The Sacrificial System and Atonement in the Pentateuch, http://newhumanityinstitute.org/pdfs/article-atonement-and-the-pentateuch.pdf. For a condensed treatment, see the blog post series on this website, “Temple Sacrifices and a Blood Thirsty God?”

[4] R.E. Averbeck, ‘Sacrifices and Offerings,’ in T. Desmond Alexander and David W. Baker (editors), Dictionary of the Old Testament: Pentateuch (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2003), p.706, italics mine; see also Christian A. Eberhart, The Sacrifice of Jesus: Understanding Atonement Biblically (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2011), p.60 – 89 and Steve Jeffery, Michael Ovey, Andrew Sach, Pierced for Our Transgressions: Rediscovering the Glory of Penal Substitution (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2007), p.44

[5] Penal substitution defender Emile Nicole, ‘Atonement in the Pentateuch,’ in Charles E. Hill and Frank A. James III (editors), The Glory of the Atonement (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004), p.43, completely neglects the eating of the sin offering, as do Steve Jeffery, Michael Ovey, Andrew Sach, Pierced for Our Transgressions: Rediscovering the Glory of Penal Substitution (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2007), p.42 – 52. Penal substitution critic Christian A. Eberhart, The Sacrifice of Jesus: Understanding Atonement Biblically (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2011), p.60 – 89 similarly neglects the motif of the priests eating the sin offering sacrifice. This neglect has significant consequences for both biblical studies and systematic theology.

[6] Thus I disagree with J. Alec Motyer, The Prophecy of Isaiah: An Introduction & Commentary (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1993), p.439 about the sin/guilt offering being about ‘reparation or compensation.’ The flaw in Motyer’s exegesis of Leviticus 5 is that he only treats the death of the animal, and assumes it to be a penal substitute straightaway. Motyer ignores the separate aspects of the blood sprinkling rite and the priests eating the flesh of the animal, culminating in the annual Day of Atonement rite with the high priest and the two goats. Because his understanding of the sin/guilt offering is truncated, his understanding of Isaiah 52:13 – 53:12 is also incomplete.

[7] J. Alan Groves, ‘Atonement in Isaiah 53’, edited by Charles E. Hill and Frank A. James III, The Glory of the Atonement (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004)